In the beginning, the Forest Service created the “21-inch rule” as one of many rules in the Eastside Screens. The “Interim Management Direction Establishing Riparian, Ecosystem and Wildlife Standards for Timber Sales”—aka the Eastside Screens—has been in place as “interim” direction since 1995. At its core, the rule says: Thou shalt not cut down a live tree larger than 21 inches in diameter measured at breast height (DBH, or 4.5 feet above the ground) on the eastside forests of Oregon and Washington.” The rule generally ended the massive liquidation of old-growth trees that had always been agency policy.

Now the Forest Service is proposing to “revise” the rule “in light of current forest conditions and the latest scientific understanding of forest management in areas that have frequent disturbances, like wildfires.” The leader of the agency effort takes great pains to say that the proposed change is narrow and surgical, and is based on the best available science. The agency has not yet publicly revealed the particular modification it will propose, but it will likely be an age-based cutoff rather than a diameter-based cutoff.

Just what age? The same age for all species? Will diameter (largeness) continue to count at all?

The 21-inch rule has both pluses and minuses. So would a rule based on age. But any rule should be based on science specific to the eastside forests and not extrapolated from science specific to the westside forests. And any rule should steer the agency to manage the eastside forests to serve their greatest need: more old trees, dead or alive.

Forest Service “Science”

The managers in the Forest Service’s National Forest System branch are relying on the scientists in the Forest Service’s research branch to produce the science to support the effort. Twelve scientists and other experts—all Forest Service employees—have produced a white paper entitled “The 1994 Eastside Screens—Large Tree Harvest Limit: Synthesis of Science Relevant to Forest Planning 25 years Later.” A problem with the white paper is that it makes numerous references to northern spotted owls. The very definition of the demarcation line between westside and eastside forests is that the former host northern spotted owls and the latter do not.

Furthermore, the white paper points out that livestock grazing, roads, and fire suppression are all problems in the eastside forests. Still, the Forest Service’s management branch has always refused—and continues to refuse—to address these issues.

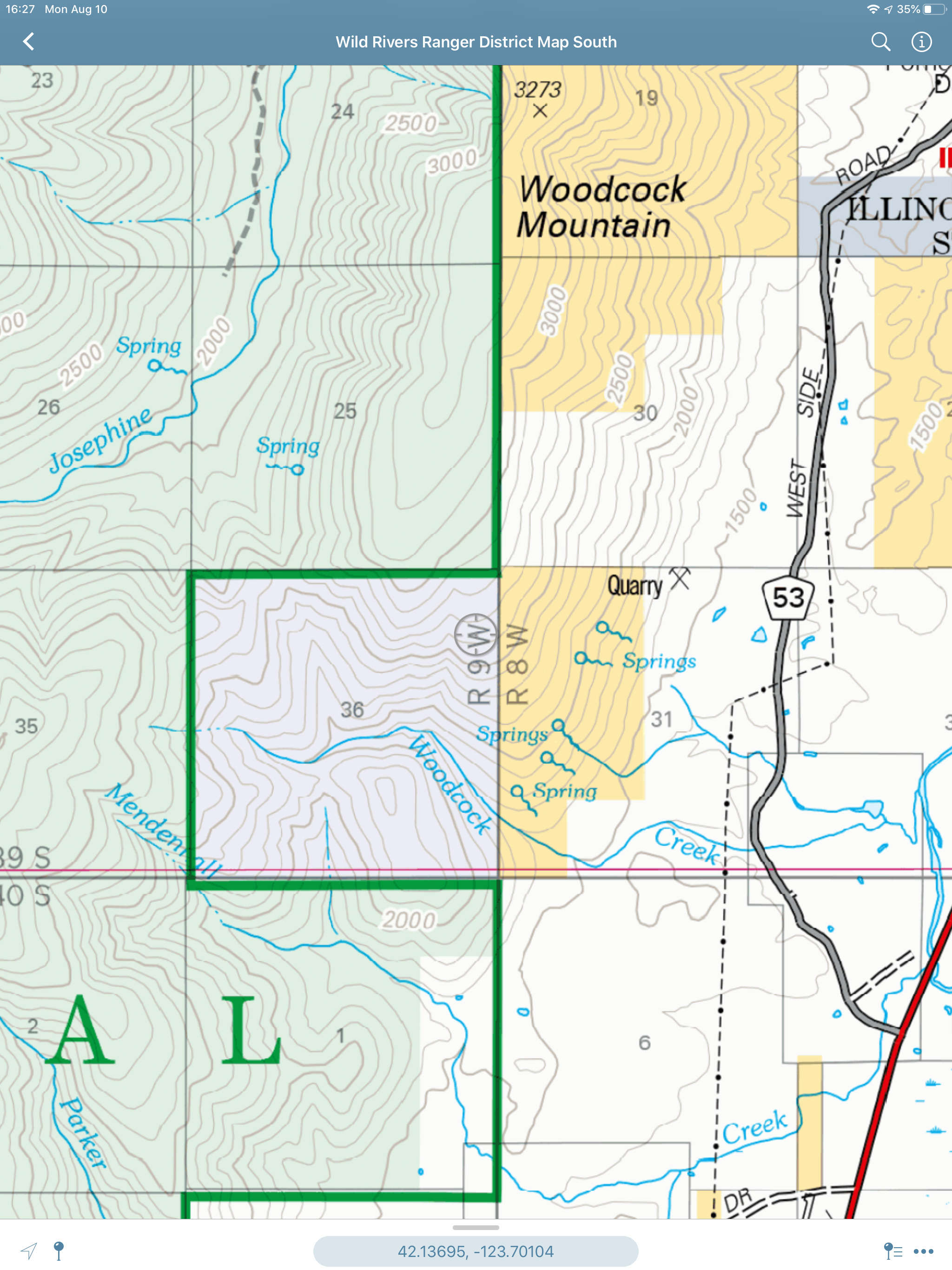

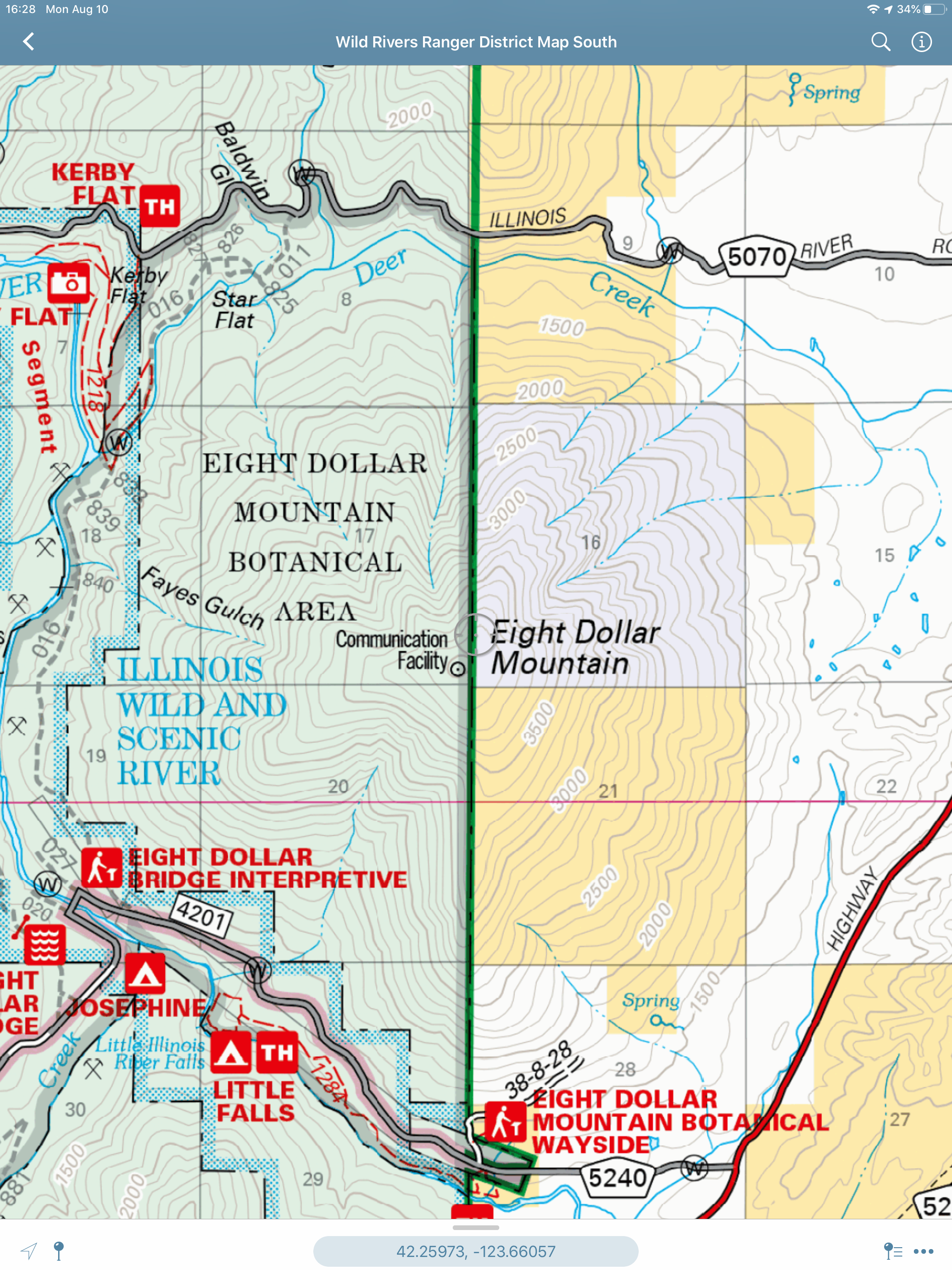

As supporting resources for the plan amendment project, the Forest Service research branch offers up two chapters from its “Synthesis of Science to Inform Land Management Within the Northwest Forest Plan Area” general technical report, noting they are “relevant to” the Eastside Screens plan amendment project. While not irrelevant, the chapters are specific to the Northwest Forest Plan area—in other words, the westside forests. The absence of northern spotted owls is evidence that the eastside forests are significantly and materially different from the westside forests.

Perhaps because they were not given adequate time, the scientists have had to phone in the science. Where is the specific eastside forest research and synthesis?

The Administrative Elegance of the 21-Inch Rule

Inherently, bureaucrats want to maximize their discretion. They don’t like hard-and-fast rules that limit their actions. Managers argue that circumstances on the ground are varied and resist a one-size-fits-all approach.

Inherently, conservationists fear agency abuse of discretion and love unambiguously clear commands that limit agency discretion. Their experience has too often been that if Congress grants the agency discretion, the agency abuses that discretion.

Inherently, scientists know the world is neither black nor white, on nor off. So scientists tend to frame recommendations to agency managers in ranges rather than absolutes (for example, a riparian buffer should be between 150 and 300 feet, depending on . . . ). While scientists are correct in acknowledging varying conditions, they fail to recognize that bureaucrats are under pressure to achieve certain outcomes (for example, to get the cut out). Given those pressures, the 150 feet in the example becomes both the floor and the ceiling.

The administrative elegance of the 21-inch rule is that anyone with a D-tape (a diameter tape measure scaled in diameter though it actually is measuring circumference) will come up with the same result. No discretion is required, so no abuse of discretion is possible.

The Limits of the 21-Inch Rule

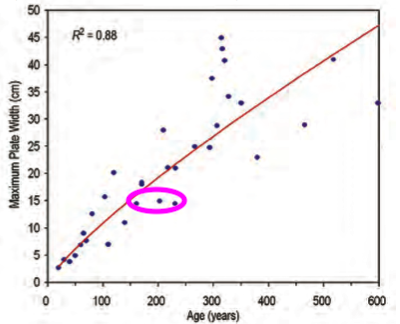

Not all old trees are large, and not all large trees are old. There is essentially a poor correlation between age and diameter (Figure 2). While trees all grow old at the same rate, trees grow large faster on more productive growing sites than on poor growing sites. In any forest, but perhaps especially in forests with fires of relatively high frequency but low intensity, both large and old are important.