When political realities come up against ecological realities, the former must be changed because the latter cannot.

Read MoreAbout That Vision Thing

Wilderness

When political realities come up against ecological realities, the former must be changed because the latter cannot.

Read MoreCongress told the Bureau of Land Management to remove a small, but fish-damaging, dam on the Donner und Blitzen Wild and Scenic River and the Steens Mountain Wilderness. The BLM may finally get around to it.

Read MoreWith a few critical tweaks, Senator Wyden’s legislation could be a net gain for the conservation of nature for the benefit of this and future generations. Without those tweaks, the bill as drafted is an existential threat to the conservation of federal public lands and should not be enacted into law.

Read MoreUnderstanding the history of public lands is useful if one is to be the best advocate for the conservation of public lands.

Read MoreNote: This is the second part of a two-part tribute to Dave Foreman, who recently shuffled off this mortal coil. Part 1 recounted Dave’s contribution to stopping the infamous Bald Mountain Road, a dagger into the heart of the Kalmiopsis wildlands in southwestern Oregon. Part 2 is my take on Dave’s unique contributions to the conservation and restoration of nature.

Figure 1. Dave Foreman never failed to give a hell of a speech. It was often more like a sermon full of information, wisdom, provocation, humor, and inspiration—but never damnation—delivered by a preacher who sought to save not human souls but life on Earth. Source: The Rewilding Institute.

The North Kalmiopsis wildlands, the lands Dave Foreman nearly lost his life trying to save from the bulldozer and the chainsaw, are still not, some four decades later, fully protected for the benefit of this and future generations. The remaining roadless wildlands have not yet been added to the Kalmiopsis Wilderness, but a good portion is somewhat administratively protected as Forest Service inventoried roadless areas. Some of the North Kalmiopsis lands have received wild and scenic river status, with more in the offing for the entire Kalmiopsis wildlands. Perhaps the mature and old-growth forests therewill be administratively protected by the Biden administration.

It can take a lot of time to save a piece of nature. Dave Foreman knew this. Dave also knew that given the rate of the human assault on nature, nature doesn’t have the luxury of time.

In my view, Dave Foreman’s greatest contributions to saving the wild were

· getting conservationists, and then society, to think bigger;

· popularizing science to save wilderness, when the science was still emerging; and

· having a large and secure enough ego to let others take credit for and run with ideas he first popularized.

Moving the Overton Window

I didn’t know it at the time, and probably neither did Dave, but Dave’s fundamental course was trying to move what the sociopolitical chattering class now calls the Overton window. The Overton window is the thinking of Joseph P. Overton of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a conservative think tank. According to Wikipedia, the Overton window is “the range of policies that a politician can recommend without appearing too extreme to gain or keep public office given the climate of public opinion at that time.”

When Dave started his conservation career, wilderness designation was within the Overton window, but generally more because of human recreation than nature conservation. Wilderness also had to encompass relatively large areas, and generally more rock and ice than low-elevation forests or desert grasslands.

The Overton window is not moved by politicians; rather it is moved by think tanks and activists who advocate for policy solutions that start outside the current range of public acceptability. As the unpopular, if not previously unspoken, idea moves to become more popular, the Overton window moves to reflect that that policy solution is now within the realm of political discussion. Politicians only look out of Overton windows.

I recall a conversation with Dave that hit home with me. The public lands conservation movement generally came out of the progressive movement, and more on Republican than Democratic wings. Early twentieth-century public lands conservationists like John Muir, Stephen Mather, Horace Albright, Gifford Pinchot, and their ilk were all white, Republican (things were different back then), and rich. They didn’t want to rock the sociopolitical boat but rather just change its course a bit. Not turn the boat around—and if any rocking was required, not too much rocking.

“Where would Martin Luther King [Jr.] have been without Malcolm X?” thundered Dave, just to me at that point, but it was a line from a speech that he had given or would give many times. The radical Malcolm X did make MLK appear more reasonable in the public arena.

Foreman helped the public lands conservation community think (and act) “outside the box,” another metaphor for the limits of public acceptability.

Dave taught me that while ecological realities are immutable, political realities are mutable. Only if one has one’s idea aperture too small and/or time horizon too short does it appear that political realities cannot be changed.

Figure 2. Dave Foreman inspired many a wildlands advocate, including John Davis, now executive director of the Rewilding Institute. Since I have known him, John has always had one foot in something big and the other in something Adirondacks. Source: The Rewilding Institute.

Presaging 30x30 . . . and 50x50

Foreman was not a scientist, but early on in his conservation career, he knew—in his gut if not yet in his head—if we’re to have functioning ecosystems across the landscape (and seascape) and over time, that at least half of every ecosystem needs to be conserved and, in some cases, restored. Later Foreman came to know this not only in his gut but also in his head. As the discipline of conservation biology emerged, Dave embraced and popularized the science that provided objective evidence for what was previously just his personal testimony.

Today, the conservation buzz is all about 30x30, or conserving 30 percent of the world’s, nations’, states’ lands and waters by 2030. Don’t tell anyone, but 30x30 is simply an interim goal on the way to 50x50, which is where the science points. Yep, 50 percent by 2050.

Urging Colleagues to Steal His Ideas

As Dave helped move nature conservation’s Overton window, he was genuinely pleased when others took credit for his work—credit either for moving the political window or for taking advantage of the concept/idea/notion/necessity that the moved Overton window exposed. More than one chief executive officer of a national conservation organization told Dave to his face that they were embracing/stealing “his” idea (of course, without crediting him). Foreman’s response was always “Go for it!” rather than “You’re welcome” and never “Hey, that’s my idea!”

While Foreman did radical things on behalf of nature, in his chest beat the heart of a reactionary deeply opposed to any so-called progress that came at a cost to the wild. It is not that he opposed civilization or was misanthropic. Rather, Foreman realized that for there to be fine cigars and exquisite liquors and the many other economic goods and services that we enjoy, and for our children to inhabit the earth and prosper, that the earth must continue to provide fundamental ecosystem goods and services.

Figure 3. In 2004, Dave made the case for rewilding (a term he coined) the continent. By today’s scientific standards, his vision was rather conservative. Dave knew the Overton window doesn’t move all at once. Source: Island Press.

So did Dave Foreman end up damning or praising me when he came to southwestern Oregon? Depending on his audience, either one. It worked for me, it worked for him, and most important, it worked for nature.

Foreman moved the needle.

Thanks, Dave.

Bottom line: No one can replace Dave Foreman. But others must and will carry on working for the wild.

For More Information

Astor, Maggie. February 26, 2019. “How the Politically Unthinkable Can Become Mainstream.” New York Times.

Foreman, Dave. 1991. Confessions of an Eco-Warrior. Crown.

———. 1992. The Big Outside: A Descriptive Inventory of the Big Wilderness Areas of the United States. Three Rivers Press.

———. 2004. Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century. Island Press.

———. 2004. The Lobo Outback Funeral Home: A Novel. Bower House.

———. 2011. Man Swarm and the Killing of Wildlife. Raven’s Eye Press.

———. 2012. Take Back Conservation. Raven’s Eye Press.

———. 2012. “The Great Backtrack,“ in Philip Cafaro and Eileen Crist (eds.), . Life on the Brink: Environmentalists Confront Overpopulation. University of Georgia Press.

———. 2014. The Great Conservation Divide: Conservation vs. Resourcism on America’s Public Lands. Raven’s Eye Press.

Rewilding Institute. “Dave Foreman (1946–2022).”

Risen, Clay. September 28, 2022. “David Foreman, Hard-Line Environmentalist, Dies at 75.” New York Times.

Wikipedia. Dave Foreman.

Zakin, Susan. September 21, 2022. “Dave Foreman, American.” Journal of the Plague Years.

A giant in nature conservation and restoration died just a few days short of the autumnal equinox. Like few others, he inspired generations of advocates of wildlands, wild waters, and wildlife to reach for the greater good and to demand more.

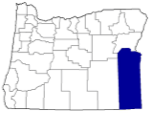

Read Morethird try may be the charm in Senator Wyden’s long effort to enact public lands legislation to conserve wildlands in the Owyhee and lower Malheur Basins in Oregon.

Read MoreBlumenauer’s bill would open up Mount Hood National Forest to new logging loopholes.

Read MoreWhile we should appreciate the greatness of great leaders, we must not ignore the things they did that were the opposite of great.

Read MoreThis is the third of three Public Lands Blog posts on 30x30, President Biden’s commitment to conserve 30 percent of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030. In Part 1, we examined the pace and scale necessary to attain 30x30. In Part 2, we considered what constitutes protected areas actually being “conserved.” In this Part 3, we offer up specific conservation recommendations that, if implemented, will result in the United States achieving 30 percent by 2030.

Top Line: Enough conservation recipes are offered here to achieve 50x50 (the ultimate necessity) if all are executed, which is what the science says is necessary to conserve our natural security—a vital part of our national security.

Figure 1. The Coglan Buttes lie west of Lake Abert in Lake County, Oregon. According to the Bureau of Land Management, it “is a dream area for lovers of the remote outdoors, offering over 60,000 acres of isolation,” and the land is “easy to access but difficult to traverse.” The agency has acknowledged that the area is special in that it is a “land with wilderness characteristics” (LWCs), but affords the area no special protection. Congress could designate the area as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System (Recipe #24), or the Biden administration could classify it as a wilderness study area and also withdraw it from the threat of mining (Recipe #1). Source: Lisa McNee, Bureau of Land Management (Flickr).

Ecological realities are immutable. While political realities are mutable, the latter don’t change on their own. Fortunately, there are two major paths to change the conservation status of federal public lands: through administrative action and through congressional action.

Ideally, Congress will enact enough legislation during the remainder of the decade to attain 30x30. An Act of Congress that protects federal public land is as permanent as conservation of land in the United States can get. If properly drafted, an Act of Congress can provide federal land management agencies with a mandate for strong and enduring preservation of biological diversity.

If Congress does not choose to act in this manner, the administration can protect federal public land everywhere but in Alaska. Fortunately, Congress has delegated many powers over the nation’s public lands to either the Secretary of the Interior or the Secretary of Agriculture (for the National Forest System), and—in the sole case of proclaiming national monuments—the President.

Potential Administrative Action

Twenty-two recipes are offered in Table 1 for administrative action by the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Agriculture, or the President. The recipes are not mutually exclusive, especially within an administering agency, but can be overlapping or alternative conservation actions on the same lands. While overlapping conservation designations can be desirable, no double counting should be allowed in determining 30x30. A common ingredient in all is that such areas must be administratively withdrawn from all forms of mineral exploitation for the maximum twenty years allowed by law.

Mining on Federal Public Lands

An important distinction between federal public lands with GAP 1 or GAP 2 status and those with lesser GAP status is based on whether mining is allowed. Federal law on mineral exploitation or protection from mining on federal public lands dates back to the latter part of the nineteenth century with the enactment of the general mining law. Today, the exploitation of federal minerals is either by location, leasing, or sale. The administering agency has the ability to say no to leasing and sale, but not to filing of mining claims by anyone in all locations open to such claiming.

When establishing a conservation area on federal lands, Congress routinely withdraws the lands from location, leasing, or sale. Unfortunately, when administrative action elevates the conservation status of federal public lands (such as Forest Service inventoried roadless areas or IRAs, Bureau of Land Management areas of critical environmental concern or ACECs, and Fish and Wildlife Service national wildlife refuges carved out of other federal land), it doesn’t automatically protect the special area from mining.

Congress has provided that the only way an area can be withdrawn from the application of the federal mining laws is for the Secretary of the Interior (or subcabinet officials also confirmed by Congress for their posts) to withdraw the lands from mining—and then only for a maximum of twenty years (though the withdrawal can be renewed). A major reason that particular USFS IRAs and BLM ACECs do not qualify for GAP 1 or GAP 2 status is that they are open to mining.

More Conservation in Alaska by Administrative Action: Fuggedaboutit!

The Alaska National Interest Lands Act of 1980 contains a provision prohibiting any “future executive branch action” withdrawing more than 5,000 acres “in the aggregate” unless Congress passes a “joint resolution of approval within one year” (16 USC 3213). Note that 5,000 acres is 0.0012 percent of the total area of Alaska. Congress should repeal this prohibition of new national monuments, new national wildlife refuges, or other effective administrative conservation in the nation’s largest state. Until Congress so acts, no administrative action in Alaska can make any material contribution to 30x30.

Potential Congressional Action

Twenty-two recipes are offered in Table 2 for congressional action. The recipes are not mutually exclusive, especially within an administering agency, but can be overlapping or alternative conservation actions on the same lands. However, they should not be double-counted for the purpose of attaining 30x30. A commonality among these congressional actions is that each explicitly or implicitly calls for the preservation of biological diversity and also promulgates a comprehensive mineral withdrawal.

Bottom Line: To increase the pace to achieve the goal, the federal government must add at least three zeros to the size of traditional conservation actions. Rather than individual new wilderness bills averaging 100,000 acres, new wilderness bills should sum hundreds of millions of acres—and promptly be enacted into law. Rather than a relatively few new national monuments mostly proclaimed in election years, many new national monuments must be proclaimed every year.

For More Information

Kerr, Andy. 2022. Forty-Four Conservation Recipes for 30x30: A Cookbook of 22 Administrative and 22 Legislative Opportunities for Government Action to Protect 30 Percent of US Lands by 2030. The Larch Company, Ashland, OR, and Washington, DC.

To permanently protect 30 percent of its lands by 2030, the US must conserve 114,183 acres of land per day—with no time off for weekends and holidays.

Read MoreFigure 1. Whitebark pine on the Fremont-Winema National Forest. Source: George Wuerthner (first appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness, Timber Press, 2004).

After decades of dithering, the Fish and Wildlife Service has finally proposed listing the species as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Read MoreFigure 1. The Coleman Rim Inventoried Roadless Area on the Fremont-Winema National Forest, somewhat protected by the Forest Service Roadless Area Conservation Rule. Source: Sandy Lonsdale (first appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness, Timber Press, 2004).

The bill still needs work if it’s to do more than merely restore the status quo prior to the Trump administration.

Read MoreIf not for the Cold War (1945–1991), there might well have been a national park in Oregon’s Cascade Mountains.

Read MoreLegislation introduced by New Mexico’s two Democratic US senators would severely undermine the integrity of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

Read MoreMalheur is the French word for adversity, misfortune, and/or tragedy. It is also, among other things, a name for a county in Oregon, a national forest, a national wildlife refuge, and a river. Senator Ron Wyden’s proposed Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act is indeed a misfortune and a tragedy.

Read MoreBuy the book. Go take a hike. Demand congressional protection.

Read MoreCompared to its political equal Washington, arch-liberal California, arch-conservative Idaho, and politically purple Nevada, Oregon has the least designated wilderness acreage and the smallest percentage of the state’s lands protected as wilderness.

Read MoreFig. 1. Crabtree Lake in Crabtree Valley, which contains some of the oldest trees in Oregon, is in the proposed Douglas Fir National Monument, located in Oregon’s Cascade Mountains. Source: David Stone, Wildlands Photography. Previously appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness (Timber Press, 2004), by the author.

Less than a week after President Trump signed the Oregon Wildlands Act into law (as one of many bills in the John D. Dingell, Jr., Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act), Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Representative Earl Blumenauer (D-3rd-OR) convened an Oregon Public Lands Forum on Monday, March 18, 2019.

Read More