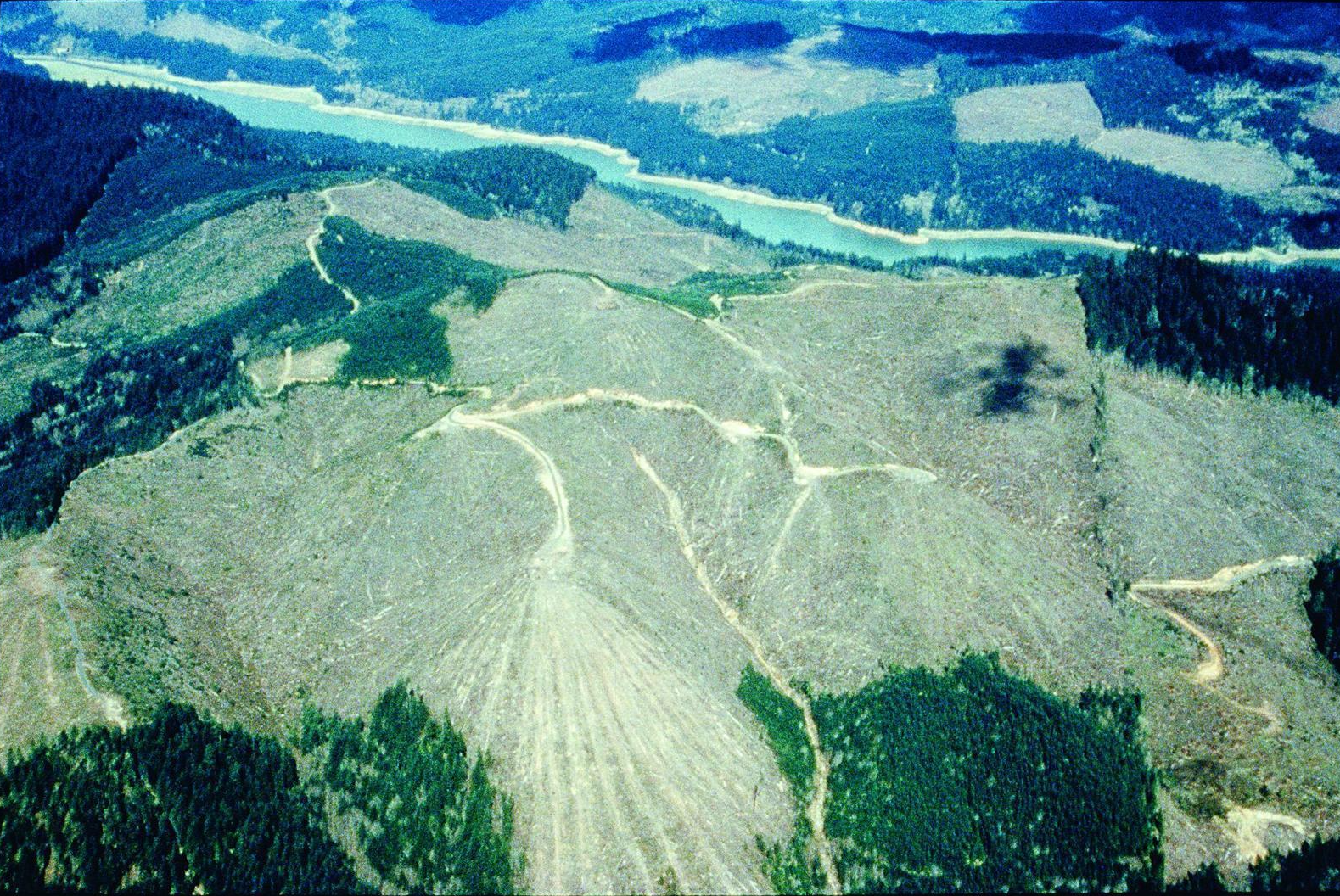

What Does the OCLA Actually Require?

What does the OCLA require of the BLM insofar as the 1937 statute relates to the “management of timber” on O&C lands? Remarkably, the courts had never clearly ruled on whether the OCLA itself contains an holtz über alles mandate. Between the BLM’s revising of western Oregon resource management plans in 2016 and President Obama’s expanding the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument in 2017, the Clearcut Conspiracy went all in on a judicial strategy to, once and for all, determine that (1) the OCLA is exalted above all other statutes, and (2) the OCLA is understood as stipulating that logging should reign supreme over all other uses.

Over the many decades since 1937, the BLM’s own lawyers (“solicitors”) have opined to varying degrees at various times that the OLCA is a “dominant use” statute where logging is superior to other uses, rather than a multiple use statute where timber supply is one use equal to the other named uses of protecting watersheds, regulating stream flow, contributing to local economic stability, and recreation. In its 2016 plan revisions, the BLM essentially still interpreted the OCLA as timber first—but tempered by all those other congressional statutes, in particular ESA and CWA (but not FLPMA).

The Clearcut Conspiracy’s legal blitzkrieg consisted of a total of six lawsuits, five of which were filed in the US District Court for the District of Columbia. As the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit explains:

The appeals arise from three sets of cases filed by an association of fifteen Oregon counties and various trade associations and timber companies. Two of the cases challenge Proclamation 9564, through which the President expanded the boundaries of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Two others challenge resource management plans that the United States Bureau of Land Management (BLM), a bureau within the United States Department of the Interior (Interior), developed to govern the use of the forest land. The final case seeks an order compelling the Interior Secretary to offer a certain amount of the forest’s timber for sale each year.

The Clearcut Conspiracy won all five cases filed in the District of Columbia at the district court level, where the conspiracy had successfully shopped for a favorable judge, but then lost all on appeal to the appeals court.

As for the sixth lawsuit, the Murphy Company and Murphy Timber Investments, LLC, filed suit in the US District Court for the District of Oregon contesting the expansion of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Murphy lost at the district court level and also in the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Clearcut Conspiracy was left with just one more option: a hail-Mary pass to the nine members of the US Supreme Court seeking review of the six cases it lost. The Supremes declined. As I speculated previously, perhaps the destructive majority on the court felt that this O&C matter was small beer compared to all the other potential damage they want to do.

In the next two Public Lands Blog posts, I examine in detail the rulings of the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (Part 2 of this series) and the US District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals (Part 3 of this series). I go so deep on these rulings because they make clear that the Clearcut Conspiracy’s fantasy that the OCLA of 1937 is a combo 11th Commandment and 28th Amendment is and always has been just that—a fantasy.