Top Line: Many bitter lemons can make quite fine lemonade, but only if the conservation community reinvents itself.

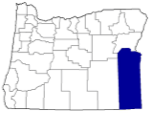

Figure 1. President Biden can proclaim an Owyhee Canyonlands National Monument on his way out the door—but only if US Senator Ron Wyden asks him to. Source: Mark List.

As I sat down the morning after the election to pen some thoughts about the existential threat that Americans just elected to a second term, I went back and reviewed my Public Lands Blog post from eight years ago entitled “The November 2016 Election: Processing the Five Stages, Then Moving On.” I wish I could be as optimistic this time.

While I fear for the atmosphere, the biosphere, the hydrosphere, global humanity, and American society, I will limit my thoughts here to the conservation of nature and the protection of the environment—most especially federal public lands. Such lands were not a significant issue in the elections but will be severely affected by the results. Unfortunately, the fate of public lands has become tied to the fate of Democrats, and the Democratic Party is likely out of power in both houses of Congress and the White House. While the election results were not a mandate to further industrialize or privatize federal public lands, more of such will nonetheless be the consequence.

In this post, I shall first analyze the policy and political landscape of the nation’s federal public lands. Second, I shall make two recommendations to the lame-duck Biden administration about what to do and not do before leaving office. Finally, and most important, I shall suggest that the American conservation community fundamentally reinvent itself to become politically relevant once again.

The Forthcoming Political Landscape

The political landscape for public lands conservation during the second Trump administration will be a combination clear-cut, toxic waste dump, and minefield. Public lands conservationists will no longer be able to rely on the rule of law—neither in making, carrying out, nor interpreting the law.

The Administration

Trump 2.0 will be exponentially more awful than Trump 1.0. Trump’s mistake during his first rampage was that he appointed at least some people both smarter than him and (most important) loyal to the Constitution. They thwarted many of the dumb, mean, and/or unconstitutional things Trump wanted to do. That will not be the case this time around. In addition, the Supreme Court has since then granted a president immunity from criminal prosecution for any official act and has thus removed another restraint against abuse of power.

Much of the public lands conservation community’s work has been to use administrative processes to seek more protection for public lands. The effectiveness of this approach peaked during the Clinton administration (1993–2001) for land and the Obama administration (2009–2017) for oceans. The first Trump administration (2017–2021) was a very large negative. The Biden administration (2021–2025) wasn’t any great shakes.

The Courts

This activist Supreme Court is increasingly making it up as they go along. If a majority doesn’t like a law as a matter of substance, they creatively reason it away despite any precedence or traditional jurisprudence. Cases are before the court that could spell the end of the National Environmental Policy Act as we have known it. Other cases that similarly jeopardize the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the National Forest Management Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, and others are likely to get the Supreme treatment.

The Congress

In re the conservation of public lands, Congress has been getting worse. Affirmative land conservation is down, while affirmative land degradation is up by even more. Almost all of the land conservation is attributable to Democrats, while the land degradation is firmly bipartisan. The main reasons for this are money in politics and gerrymandering of congressional districts.

Gerrymandering, while a bipartisan plague, is done most effectively by Republicans. The result is that most members of Congress of both parties have extremely safe seats and are easily elected in the general election. If a seat is threatened, it’s only in a partisan primary. The Democrats take the public lands conservation community for granted, and the Republicans take us to the cleaners.

Earth to Biden Administration: For the Love of Nature, Do Nothing except One Thing

The Biden administration is set to finalize several policy initiatives that pertain to public lands, wildlife, the climate, and/or the environment. Among these are initiatives regarding old growth in the national forests, greater sage-grouse, and management of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The Biden administration should not finalize any of them. Put down the policy pen and step away.

Do Nothing!

You may be thinking, Is not half a loaf better than none? Actually, no.

Across the board, the conservation policy initiatives I’ve mentioned are very weak tea, if not bitter pills. For example, the Biden administration proposals for old-growth forests and greater sage-grouse would be a net loss for their conservation. In re the former, unbelievably, the Forest Service proposal to amend its forest management plans will result in a loss in both quality and quantity of old-growth forests. In re the latter, the prospective Biden 2024 sage-grouse plan is worse than the 2015 Obama sage-grouse plan and may not be much better the 2019 Trump sage-grouse plan.

Lest you believe such stale heels are better than half a loaf, let me tell you about the Congressional Review Act (CRA). The Congressional Research Service describes the CRA as “a tool Congress can use to overturn certain federal agency actions.” The CRA disapproval process can apply to almost any federal “rule” (including federal land and/or resource management plans) that is finalized within a specified period. For this 118th Congress, any rule finalized after August 1, 2024, is subject to a “lookback” provision when the 119th Congress convenes in January. If it were President Harris, she’d veto any joint resolution of disapproval (JRD) of a Biden rule. But it’s not.

If a CRA JRD is filed, it may receive special consideration in the House of Representatives and must receive such in the Senate. The procedure calls for a clean (no amendments) up-or-down vote in the House and Senate (where it is not subject to a filibuster that requires sixty votes to overcome). If a JRD passes both houses, it is presented to the president for signature or veto.

The Congressional Research Service explains the noose and the salting of the earth that applies to a disapproved rule:

A rule that is the subject of an enacted CRA joint resolution of disapproval goes out of effect immediately if the rule has already taken effect when the resolution of disapproval is enacted and “shall be treated as though such rule had never taken effect.” If the rule has not yet gone into effect when the resolution of disapproval is enacted, it will not take effect.

In addition, a rule subject to an enacted joint resolution of disapproval “may not be reissued in substantially the same form, and a new rule that is substantially the same . . . may not be issued, unless the reissued or new rule is specifically authorized by a law enacted after the date of the joint resolution.” [emphasis added]

So not only do we not want the Biden administration issuing weak and lame environmental rules, we also sure as hell don’t want Congress disapproving such rules and forbidding any future administration from doing another rule that is “in substantially the same form.”

Except One Thing: National Monuments

Proclamations by the president of new or expanded national monuments with the authority granted by Congress pursuant to the Antiquities Act of 1906 are not rules subject to the Congressional Review Act. Biden needs to proclaim a boatload of new national monuments. And not just a few, but severalfold more than he was contemplating before the election, with some zeros added to the acreages.

While not subject to the CRA, national monument proclamations are subject to an activist Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Roberts has written that he’s fishing for a case to gut the Antiquities Act (as the Supreme Court has gutted the Voting Rights Act and others).

If failing to act is the right course for Biden’s (wimpy) environmental rules to not get CRAed, is it not the same with national monuments? No. National monuments are quite popular, and it would be unpopular even for a popularly elected president to reverse national monument designations. If Trump is going to reverse Biden’s monuments (or the Supremes are going to gut them), they need to be made to do it out loud and in public.

Earth to Conservation Organizations: Restructure for a Changed Political Landscape

Continuing to rely on the administration, the courts, or Congress as they are now constituted to elevate the conservation status of public lands is a fool’s errand. What used to work well for the conservation community no longer does and will not again until the makeup of these federal branches changes. Such change can only come with better election results.

If I were in charge, I would institute a plethora of reforms regarding election to government office and the operation of government.

See Public Lands Blog post: “Small-d Democratic Reforms to Revive Our Republican Form of Government”

Since I’m not in charge, please permit me to suggest that conservation organizations need to fundamentally reorganize themselves to become politically relevant once again.

To conserve federal public lands, it’s now all about elections. It’s no longer about commenting on draft environmental impact statements. But due to some quirks of conservation history, most conservation organizations are organized under federal tax law in ways that prevent their effective engagement in political and election advocacy.

Most conservation organizations are organized under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. This tax status allows the organization to avoid paying taxes on its income and allows the donor to take a tax deduction for contributions to the organization. The cost of these two benefits is that the organization can only seek to influence legislation in very limited ways and cannot seek to influence elections in any way. To avoid income taxes, these organizations waive part of their First Amendment rights and most of their effectiveness.

There is another tax status, 501(c)(4), that allows the organization to avoid taxation on its income but does not give the donor a tax deduction for contributions to the organization. A “c4” can use all its funds for lobbying or influencing elections. In addition, a c4 doesn’t have to disclose the names of its donors.

While some c3s have affiliated c4s, those c4s are always much smaller than the c3 and are dusted off only briefly every two to four years for elections. In the rest of the public interest advocacy universe, organizations have a c4 as their mothership and a smaller affiliated c3 for taking in foundation money and/or large contributions from donors who insist on getting a tax deduction.

You may want to ask any conservation organization you contribute to if it is a c3 or a c4—or both. Increasingly, I’m no longer contributing to c3s but rather to c4s.

See Public Lands Blog post: “The Public Lands Conservation Movement: Mis-organized for Job #1”

In Conclusion

Here are a few excerpts from what I wrote in November 2016, followed by my thoughts today.

On this day-after I am working through my five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, grieving and acceptance. The thing about these stages is they don’t have to come in a particular order and can be repeated.

Nothing has changed eight years later.

I’m going to take a long walk with my dog and ponder next steps. A bad election outcome will cause one to change strategies and tactics, but not goals.

I took that walk but with a new puppy (that looks quite a bit like the old one) and it was 8.2 miles that day as Lucy needed wearing out and I needed refreshing.

I’ve been around long enough to remember the dark days of the Reagan Administration and the dark days of the G.W. Bush Administration. The days of Trump may be darker. In previous dark times, the Democrats generally held at least one house of Congress and served as a check on the excesses of Reagan and Bush, as did the federal courts.

This time a Republican President can sign legislation passed by a Republican House of Representatives and a Republican Senate. The only check is the Senate rule that requires 60 out of their 100 votes to end debate (aka filibuster).

Trump 1.0 was hell for the conservation of public lands. Trump 2.0 will likely be as bad or worse.

I’m willing to bet that if the House also goes Republican, as is expected, the Senate filibuster will go away. As we have been taught once again, elections matter.

In two years, there’s another election. All House members and one-third of senators will be on the ballot.

Bottom Line: The conservation community needs to fundamentally reorganize itself to matter in elections.