Top Line: This third try may be the charm in Senator Wyden’s long effort to enact public lands legislation to conserve wildlands in the Owyhee and lower Malheur Basins in Oregon.

Figure 1. Parts of the Owyhee River in Oregon are in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System and/or the Oregon State Scenic Waterways System. However, much of the Oregon portion of the basin has no permanent conservation status. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives.

On September 15, Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) introduced his proposed Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act, aka the Malheur CEO Act (S.4860, 117th). Its official synopsis:

To provide for the establishment of a grazing management program on Federal land in Malheur County, Oregon, and for other purposes.

Fortunately, those “other purposes” include a significant amount of new wilderness. They also include other purposes of lesser value. To conservationists, it’s a wilderness bill, and more (or less, depending on your point of view). To public lands grazing permittees, it’s a long-sought change in how they can graze Bureau of Land Management (BLM) holdings in Malheur County, with some wilderness the price to get it.

Since 2017, Wyden has introduced several pieces of legislation pertaining to public land conservation and development on Bureau of Land Management holdings in Malheur County, Oregon. I was critical of those earlier efforts, and my critiques can be found in the Public Lands Blog posts “Owyhee Canyonlands: Faux Conservation and Pork Barrel Development” (August 2017), “L’Affaire Malheur, Part 1: The Proposed Legislation” (January 2020), and “L’Affaire Malheur, Part 2: Backstory and Analysis” (January 2020).

However, when reviewing public lands legislation, it is my policy to consider any new legislative language anew and not be anchored or prejudiced either by previous iterations or by my previous utterances. So let’s take a fresh look. Is the legislation a net gain for conservation? If so, how much? What are the negatives? How could the language be improved by either deletion or addition?

Map 1. Disposition of wilderness-quality lands in S.4860. More than 1.13 million acres of Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) and Lands with Wilderness Characteristics (LWCs) become wilderness, while some other WSAs are “release[d] from protection” and some LWCs are left by the wayside. Large expanses of WSAs in Malheur County are unaffected by this legislation. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Section by Section

Let’s go through the bill piece by piece.

Section 1 Short Title

See above.

Section 2 Definitions

Key terms are defined. The legislation pertains to all BLM-administered lands in Malheur County, Oregon.

Figure 2. Domestic livestock have wrought more ecological havoc than bulldozers and chainsaws combined. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Section 3 Malheur County Grazing Management Program

Establishes a Malheur County Grazing Management Program to allow for increased “operational flexibility” in grazing use to account for changing landscape conditions and to “improve the long‐term ecological health of the Federal Land,” in accordance with existing law and regulations.

Section 4 Malheur Community Empowerment for Owyhee Group

Establishes the “Malheur Community Empowerment for Owyhee Group” (“Malheur CEO Group”), composed of eight voting and four non‐voting members to be appointed by the Secretary from recommendations of the Malheur County Board of Commissioners and the BLM Vale District Manager to provide advice and recommendations on the implementation of the Malheur County Grazing Management Program. Exempts the CEO Group from the Federal Advisory Committee Act.

Figure 3. The bill would establish, among many others, the Upper Leslie Gulch Wilderness. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon Archives.

Section 5 Land Designations

Establishes New Wilderness Areas

The bill would establish twenty-nine new wilderness areas, totaling 1,133,841 acres, to wit (Map 1):

• Fifteenmile Creek Wilderness (58,599 acres)

• Oregon Canyon Mountains Wilderness (57,891 acres)

• Twelvemile Creek Wilderness (37,779 acres)

• Upper West Little Owyhee Wilderness (93,159 acres)

• Lookout Butte Wilderness (66,194 acres)

• Mary Gautreaux Owyhee River Canyon Wilderness (223,586 acres)

• Twin Butte Wilderness (18,135 acres)

• Cairn “C” Wilderness (8,946 acres)

• Oregon Butte Wilderness (32,010 acres)

• Deer Flat Wilderness (12,266 acres)

• Sacramento Hills Wilderness (9,568 acres)

• Coyote Wells Wilderness (7,147 acres)

• Big Grassy Wilderness (45,192 acres)

• Little Groundhog Reservoir [sic] Wilderness (5,272 acres)

• Mary Gautreaux Lower Owyhee Canyon Wilderness (79,947 acres)

• Jordan Crater[s] [sic] Wilderness (31,141 acres)

• Owyhee Breaks Wilderness (29,471 acres)

• Dry Creek Wilderness (33,209 acres)

• Dry Creek Buttes Wilderness (53,782 acres)

• Upper Leslie Gulch Wilderness (2,911 acres)

• Slocum Creek Wilderness (7,528 acres)

• Honeycombs Wilderness (40,099 acres)

• Wild Horse Basin Wilderness (18,381 acres)

• Quartz Mountain Wilderness (32,781 acres)

• The Tongue Wilderness (6,800 acres)

• Burnt Mountain Wilderness (8,109 acres)

• Cottonwood Creek Wilderness (77,828 acres)

• Castle Rock Wilderness (10,519 acres)

• Beaver Dam Creek Wilderness (19,080 acres)

Figure 4. The Oregon conservation community owes much to Senator Wyden’s longtime staffer and friend Mary Gautreaux. Source: Twitter.

Wilderness areas are mostly named after geographic features, but sometimes they honor people. The late, great Mary Gautreaux was a longtime staffer and friend to Wyden who deserves every one of the acres of the two new Oregon wilderness areas named for her.

Releases Existing Wilderness Study Areas

The legislation would release 208,521 acres of long-established wilderness study areas (WSAs) from the interim protection they have enjoyed since their designation in the 1980s. (The BLM is mandated to “manage such lands . . . in a manner so as not to impair the suitability of such areas for preservation as wilderness.”)

Fails to Designate Lands with Wilderness Characteristics

The bill fails to establish any wilderness from ~856,000 acres of BLM-identified lands with wilderness characteristics (LWCs).

Figure 5. The legislation would require various economic development studies, several of which are focused on the Owyhee Reservoir, a 53-mile-long human-made seasonally fluctuating slackwater. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon Archives.

Section 6 Economic Development

Various projects and schemes would be facilitated, or at least studied, with federal dollars, including these:

• upgrading the road to Owyhee Dam

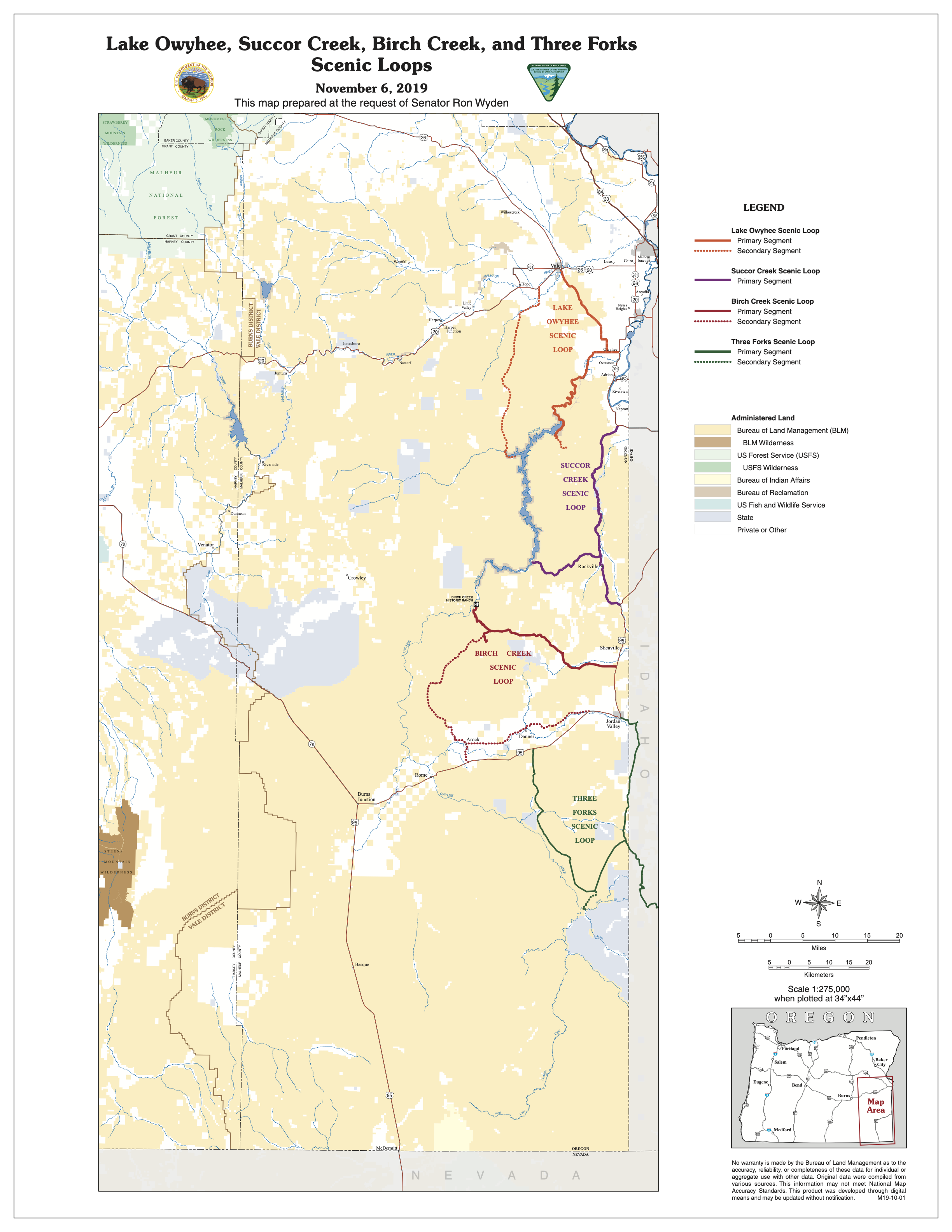

• upgrading the Succor Creek , Birch Creek, and Three Forks Scenic Loop Roads (Map 2)

• studying the feasibility of establishing “not more than 2” marinas on Owyhee Reservoir

• studying the feasibility of making improvements to existing Oregon state parks on Owyhee Reservoir

• studying the feasibility of establishing “a network of hostelries in the County using former hotels and bunkhouses that are not currently in use”

• the feasibility of making improvements to private camps on the shore of Owyhee Reservoir

• studying the feasibility of establishing a dude ranch at Birch Creek

Map 2. Under the legislation some existing roads would be upgraded and marketed. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

• studying the feasibility of “any other economic development proposals for the Owyhee Reservoir or the County” (I’m thinking a paddle bar on “Lake” [sic] Owyhee)

• studying the feasibility of establishing a rails-to-trails project known as “Rails to Trails: the Oregon Eastern Branch/The Oregon and Northwestern Railroad”

• studying “how best to market communities or sections of the County as the ‘Gateway to the Oregon Owyhee’”

• studying the need to use the Jordan Valley Airstrip for firefighting

Figure 6. The Owyhee Dam looms large, literally and figuratively, in Malheur County. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon Archives.

Section 7 Land Conveyance to the Burns Paiute Tribe

Transfers into trust 6,686 acres of private land and 21,548 acres of federal land for the Burns Paiute Tribe. Requires the Secretary to enter into agreement with the State of Oregon to conduct exchanges for state‐owned inholdings.

Section 8 Effect on Tribal Rights and Certain Existing Uses

States that nothing in this Act alters, modifies, enlarges, diminishes, or abrogates rights secured by a treaty, statute, Executive order, or other Federal law of any Indian Tribe, including off‐reservation reserved rights.

Figure 7. The proposed Jordan “Crater” Wilderness is in the bill, though with a typo: it should be “Craters.” Volcanically speaking, Jordan Craters may well not be extinct. Scientists have discovered 18 acres of the bare lava that’s really bare—no lichens and mosses. That means this part of the flow is less than ~130 years old, although there is no record of an eruption. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

The Good

Of course, the unalloyed good is the establishment of more than one million acres of new wilderness areas in Oregon. If enacted into law, it would be the single largest wilderness bill for Oregon ever enacted by Congress.

The Not Good

Release of Wilderness Study Areas

Though the wilderness study area (WSA) designation is only an “interim” congressional status, such areas are protected by some significant amount of mandated conservation. WSAs are part of the National Landscape Conservation System (which could use some improvement; see the Public Lands Blog post “The National Landscape Conservation System: In Need of Rounding Out”). The WSAs will be opened to the BLM’s “multiple-[ab]use management.”

Omits Lands with Wilderness Characteristics

While only inventoried and not protected in any way, LWC status could have been an avenue to enhanced conservation for these lands, but S.4860 declines to do so. This is a missed opportunity of major proportions.

A “Malheur County Grazing Management Program”

As if having always devoting almost all of the staff and funding of the BLM’s Vale District office to grazing is not already enough of a grazing management program for Malheur County! No good for the land can come from a specially congressionally mandated program. The legislation would embed into statute a BLM instruction memorandum that furthers “outcome-based grazing,” which is code for public land grazing permittees having even more control over the public lands than they have now.

A Special-Interest Advisory Committee

The “Malheur CEO Group” is essentially a federal advisory committee, yet the legislation would expressly exempt it from the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which along with the Freedom of Information Act, the Government in the Sunshine Act, and the Administrative Procedure Act are the four pillars of open and transparent government.

Recreation and Economic Development

Unrestrained, increased recreation and economic development is harmful to nature. Restrained, such development can be benign or even positive—if it develops a conservation-minded constituency of people who care about conserving the areas they visit. Some of the enumerated projects to be evaluated make sense, while others do not.

Tribal Land Transfer

That the Burns Paiute Tribe have a larger reservation than they now have is just. However, rather than diminishing the federal asset base of which the nation’s public lands are a part, Congress should appropriate money to be given directly to the Tribe to do with what they want—including empowering the Tribe to buy unoccupied nonfederal lands of their choice. Rather than the BLM giving more public land to the State of Oregon in exchange for 4,137 acres of state lands that would also go into trust for the Tribe, Congress (I’m talking to you, Senator Merkley, chair of the appropriate subcommittee on the Appropriations Committee) should just write a check to the Common School Fund for the state lands along the Malheur River to go into trust for the Burns Paiute Tribe. At perhaps $1,000 per acre average value, we’re talking a little more than $4 million. BLM land exchanges take extraordinary amounts of time and therefore money.

The last thing the Oregon State Land Board wants is to trade some of its most severely underperforming land asset (rangelands) for more rangelands.

Figure 8. The road (you can see it if you look closely on the left bank) along the Owyhee River below Owyhee Dam would be improved under the legislation. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

The Missing

No Voluntary Grazing Permit Retirement Provision

Though Senator Wyden has included a voluntary federal grazing permit retirement facilitation provision in previous Oregon public lands conservation bills he enacted into law (for example, for Steens Mountain, Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, and Oregon Caves National Monument), no such provision can be found here. Cosponsor Merkley has such in his pending Sutton Mountain National Monument legislation (see the Public Lands Blog post “The Proposed Sutton Mountain National ‘Monument’”). Voluntary grazing permit retirement is ecologically essential, economically rational, fiscally prudent, socially just, and politically pragmatic.

No Protection for Areas of Critical Environmental Concern

Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (ACECs) are defined in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) as

areas within the public lands where special management attention is required (when such areas are developed or used or where no development is required) to protect and prevent irreparable damage to important historic, cultural, or scenic values, fish and wildlife resources or other natural systems or processes, or to protect life and safety from natural hazards.

ACECs are the crown jewels of the BLM public lands (see the Public Lands Blog post “BLM Areas of Critical Environmental Concern: Crown Jewels Open to Theft”). Malheur County, Oregon, encompasses twenty-eight ACECs, totaling 206,917 acres, on BLM lands. Six were established in 1983, the remainder in 2002. These and most other ACECs are vulnerable to industrial-scale strip mining, fossil fuel exploitation, and other threats. This legislation should protect the ACECs in Malheur County from all forms of mineral exploitation and also include them in the National Landscape Conservation System (see the Public Lands Blog post “The National Landscape Conservation System: In Need of Rounding Out”).

No Ban on Fossil Fuel Development

The only federal public lands anywhere in Oregon that have been leased for fossil-fuel development are 172,759 acres of BLM lands in Malheur County. None are producing; all are being held for speculation (lots of leases on the books makes the company more attractive to investors). Since Wyden’s legislation affects all BLM lands in Malheur County, it is appropriate to ban any new fossil-fuel leasing anywhere on those lands. Fossil fuels are so twentieth century.

Monumental Opportunity

Back to my initial questions:

• Is the legislation a net gain for conservation? Yes.

• If so, how much? It could be a lot better if ACECs were adequately protected and fossil fuels banned. Note that these two conservation improvements would have no effect on public lands livestock grazing.

• What are the negatives? See above.

• How could the language be improved by either deletion or addition? See above.

You wouldn’t know it, but Senator Wyden is actually up for re-election this year. His Republican opponent is so nothing that media coverage of her is almost nil. A shout-out to Republican challenger Jo Rae Perkins, a perennial losing candidate who, according to Wikipedia, “has received national attention for her belief in QAnon.” Wyden will win his re-election for another six-year term in 2022. At seventy-three, he could be running in his last election. However, given Wyden has eighteen colleagues in the Senate older than him, one never knows.

In any case, most elected officials at that stage of their career are somewhere along the legacy-mode spectrum. I am reminded of something Wyden’s predecessor, Senator Bob Packwood (see my Public Lands Blog pre-remembrance of Packwood), once told me. He’d rather be remembered for Hells Canyon, French Pete, Cascade Head, and Oregon Dunes than for the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Packwood chaired, and Wyden chairs, the Senate Finance Committee. Wyden is powerful enough in the Democrat-controlled Senate to get his Owyhee bill through the Senate. Powerful enough that he could enact even stronger conservation protections than afforded by the current bill and bolster his conservation legacy.

The bill should pass this Congress while the Democrats still control the House of Representatives. If four (or even three; I’m not looking at you, lame-duck Representative Kurt Schrader) of the five members of the House delegation from Oregon come out in favor, along with the chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources, Representative Raúl Grijalva, it is likely the House will accept the Senate-only-passed Owyhee bill as part of a large omnibus package.

If the Republicans take the House in the next (118th) Congress, Representative Cliff Bentz (R-OR-2nd) will have a lot more to say about any public lands bill in his district. The new Oregon 2nd District encompasses nearly three-quarters of the land area of the state (and an even greater proportion of federal public lands in Oregon.) If the Owyhee bill doesn’t make it this Congress, it will be up to the public lands ranchers and economic development aficionados in Malheur County to persuade Rep. Bentz to support the legislation in the next Congress.

Although I like the wilderness designations in the bill, part of me hopes this bill dies, as no good will come from a special Malheur County Grazing Management Program.

Fortunately for the Owyhee wildlands, an alternative to congressional legislation is presidential proclamation.

When President Biden reversed President Trump’s eviscerations of the Grand Staircase–Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments in Utah, Biden didn’t just reinstate the proclamations of Presidents Clinton and Obama respectively, but in several ways strengthened the proclamation protections—including by adding a voluntary federal grazing permit retirement provision. Here’s the language for Grand Staircase–Escalante (essentially identical for Bears Ears):

Should grazing permits or leases be voluntarily relinquished by existing holders, the Secretary shall retire from livestock grazing the lands covered by such permits or leases pursuant to the processes of applicable law. Forage shall not be reallocated for livestock grazing purposes unless the Secretary specifically finds that such reallocation will advance the purposes of this proclamation and Proclamation 6920.

I’m pretty confident that any national monument proclamation wouldn’t include a Malheur County Grazing Management Program.

For More Information

• Kerr, Andy. 2000. Oregon Desert Guide: 70 Hikes. Seattle: Mountaineers Books.

• Oregon Natural Desert Association. Owyhee Canyonlands (web page).

• USDI Bureau of Land Management. 2018. Flexibility in Livestock Grazing Management (web page), Instruction Memorandum IM 2018-109.

Bottom Line: With a few tweaks, Senator Wyden’s Owyhee legislation could serve as a cornerstone of the conservation legacy he leaves for Oregonians.