It was only three years ago that Big Timber had its champagne chilling on ice. The Elliott State Forest (ESF) was about to be sold to a timber syndicate that would promptly liquidate almost all of its remaining old trees. However, the State Land Board (SLB)—a constitutional body consisting of the state’s three highest elected officials: the governor, the secretary of state, and the state treasurer—reversed their privatization course in the nick of time and decided that the ESF would remain in “public” ownership.

Why the reversal? There was a massive outpouring of outrage from the public. In contrast to the era a generation before (1989±10 to 1995±10) when the Pacific Northwest forest wars centered on the liquidation of most of the region’s remaining old-growth forests, in 2016 Oregonians were no longer divided about logging native forest stands on the state’s “public” lands. Now Oregonians have a chance to help the SLB decide whether to turn over management of the ESF to Oregon State University’s College of Forestry. Public comments are due by 5 PM on November 29.

Figure 2. Trees in the Elliott State Forest. Though not particularly old, they are particularly large thanks to fine growing conditions. Source: Francis Eatherington.

Some Background: Decoupling the ESF from the Common School Fund

The ESF is an asset of Oregon’s Common School Fund (CSF), which is constitutionally dedicated to making money to support K–12 public education. Besides the Elliott, ~39,000 acres of other forestlands mostly in western Oregon and ~620,000 acres of “rangelands” in eastern Oregon are also assets of the CSF. The SLB administers the CSF as a trust whose beneficiaries are the schoolchildren of Oregon. (The decline in timber sale profits is what made the SLB toy with privatizing the ESF). While CSF lands offer public values and public access, they are not public lands. A major goal of the public land conservation community is to decouple the ESF (and eventually all similar lands) from the CSF so they are truly public lands.

Figure 3. Not truly public lands. Alas, half of the Elliott State Forest has been roaded and clear-cut. Source: Francis Eatherington.

In May 2017, the SLB voted to keep the Elliott State Forest in public ownership and directed the Oregon Department of State Lands to move forward with this aim in mind. The ODSL began to explore decoupling the forest from the Common School Fund and finding the best permanent administrative home for it. Despite its name, the ODSL is merely an asset manager, not a land manager, and sees the ESF as a very underperforming and highly problematic asset. Many other investments can grow faster than investments in trees—and don’t have the public yelling at you.

The ODSL had long outsourced management of the ESF to the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) until it canceled the contract in the wake of the privatization scandal, which was catalyzed by the ODF violating the federal Endangered Species Act by killing ESA-listed species. If the timber über alles culture of the ODF wasn’t enough, ODSL finally realized that ODF was also charging excessive management overhead costs.

State officials briefly considered handing management to the department of state parks (OSPD) or fish and wildlife (ODFW) but soon rejected those ideas, as both are rather moribund bureaucracies that have neither the vision nor the competence to administer the ESF in the twenty-first century.

The US Forest Service had expressed initial interest in returning the Elliott State Forest to the Siuslaw National Forest from whence it came, but the election of Donald Trump in 2016 killed that option. (The ESF came into being early in the twentieth century after a land exchange where the State of Oregon and the Forest Service traded out almost all of the sections in each township that the federal government granted the state upon achieving statehood in 1859 that fell within national forest boundaries.)

Figure 4. An old-growth tree in the Elliott State Forest that survived the generally stand-replacing fire of 1868 (152 years ago). Source: Francis Eatherington.

To his great credit, State Treasurer Tobias Read (D) reached out to Oregon State University (OSU) and asked if it would consider the option of an Elliott State Research Forest (ESRF). OSU stepped up and said it would consider it. The ODSL then established a stakeholder advisory committee, and for the last few years the ESRF option has been explored and developed. The OSU College of Forestry (OSUCF) has been beavering away on a draft proposal, which is now out for public review and comment before being taken up at the SLB’s December 8 meeting.

Figure 5. Salmon fry in the Elliott State Forest. Source: Francis Eatherington.

The Elliott State Research Forest Proposal: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The OSUCF proposal is not fully developed. Some of its recommendations are quite laudable, while others are quite laughable. Let’s briefly visit just a few of the highlights and the lowlights.

The Good

According to the Audubon Society of Portland, the draft OSUCF ESRF plan would do these good things:

• Protect more than 90 percent of the older trees (>65 years of age) in permanent reserves.

• Place 66 percent of the entire forest (54,154 acres) in permanent reserves (Figure 6).

• Create a 30,000+ acre contiguous reserve area representing more than 40 percent of the entire forest.

• Include significantly stronger riparian protections than the Oregon Forest Practices Act.

• Protect trees and stands greater than 152 years of age, which predate the 1868 stand-replacement fire.

• Allow for more than 70 percent of the Elliott to be mature forest in fifty years, as compared with approximately 50 percent today.

• Prescribe sixty-year rotations in harvest areas (Big Timber usually does forty years).

• Ban the use of rodenticides to kill mountain beaver and other wildlife on the Elliott.

• Create the opportunity for significant research on a wide array of important topics.

• Increase opportunities for recreation on the Elliott.

• Fully decouple the Elliott from the Common School Fund, which would eliminate the anachronistic structure of tying school funding to timber harvest.

• Create real potential to bring together historically antagonistic stakeholders in a new era of collaboration for the Elliott.

I generally concur.

Figure 6. Under the current proposed ESFR, 65% would be dedicated to nature (in the form of “controls” for their experiments), 18% to an approximation of standard industrial plantation “forestry”, and 17% to various intensities that have variously and previously been described as ecological forest management, ecoforestry, new forestry, kinder-and-gentler clear-cuts, etc. Source: OSU College of Forestry.

The Bad

Again, according to Portland Audubon:

• Clear-cutting would continue on approximately 14,579 acres (18 percent) of the Elliott. All stands would be less than sixty-five years old and the harvest would be done on sixty-year rotations and would include riparian buffers.

• Selective harvest would proceed on 14,654 acres, which includes approximately 3,200 acres of older forest (65 to 162 years old) encompassing some marbled murrelet habitat.

• Very limited aerial spraying would be allowed (only where other methods are not practicable) in clear-cuts.

Again, I generally concur. Even when considering the ugly (see below)—quantitatively and qualitatively, the ugly is merely the baddest of the bad— the good far outweighs the bad.

The Ugly

My three key concerns about the OSU proposal are

• its fundamental research framework (emphasizing share versus spare, which is a research focus better suited to the 1920s than 2020s);

• its mischaracterization of the ESRF as a “working forest”; and

• the ability of OSU’s College of Forestry to administer an ESRF.

Each concern is worth exploring in greater detail.

Figure 7. A figure from the draft plan, captioned “Size of the four largest wilderness areas in the Oregon Coast [Range] as compared to the Conservation Reserve Watershed. The CRW and the Devils Staircase Wilderness Area are adjacent and represent a 65,246 acre reserve, the largest in the Oregon Coast Range.” Actually, the CRW would be ~30,000 acres, and there is the matter of Oregon Highway 38 bifurcating the joint reserve. Nonetheless, the CRW would be a tremendous conservation asset. Source: OSU College of Forestry.

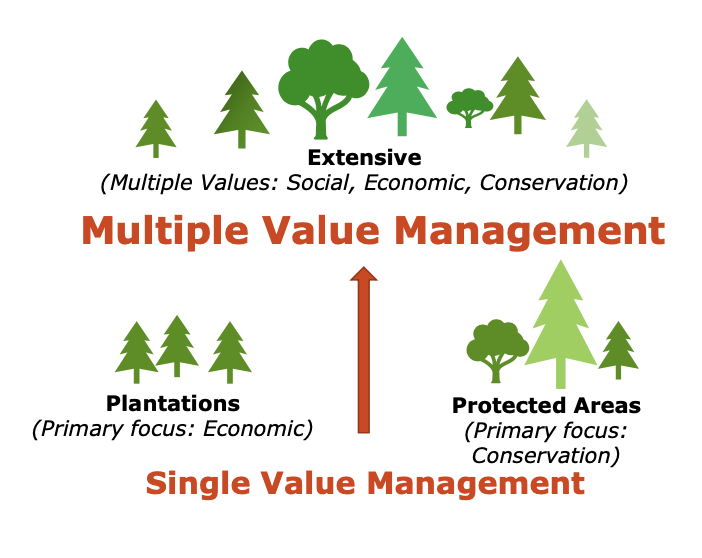

Share or Spare?

There has long been a debate in forestry and conservation circles about whether, given a need for x amount of fiber or food (a nonnegotiable number in the discussion), ’tis better to spread the logging or crops broadly across or within the forest landscape (“share”) or to concentrate and intensify production in as little area as possible (“spare”) and save the rest for nature (Figure 8). While the debate has been long, it’s over. For nature, it’s best not to share the damage across the landscape but to spare as much of the landscape as possible. In a 2018 paper entitled “What Have We Learned from the Land Sparing-Sharing Model?” scientist Ben Phalan wrote:

The key finding from all empirical studies to date, covering >1500 species, is that most species would have larger populations if a given amount of food is produced on as small an area as possible, while sparing as large an area of native vegetation as possible.

Figure 8. the OSUCF proposes yet another share versus spare experiment because it didn’t like the earlier answer. Share versus spare has been decisively answered to the satisfaction of ecologists, but not of foresters: single value management is best for nature. However, it’s bad for the profession of forestry as it would be relegated solely to pesticide- and fertilizer-fueled short-rotation monoculture plantation forestry where foresters are the running dog lackies of Wall Street. Even worse, more fiber could end up coming from farmlands. Source: OSU College of Forestry.

Several scientific papers have directly addressed the issue and concluded that it is better for forests to have the fiber come from as few acres of plantations as possible (Sedjo and Botkin 1997, Binkley 1997, Edwards et al. 2014). Nonetheless, the OSUCF is proposing a multitude of small watersheds allocated to a “triad” of logging intensities (Figure 9): “reserves” (no logging), “extensive” (cutting 20 percent, 40 percent, 60 percent, or 80 percent of the trees), and “intensive” (intense clear-cutting). With irony I must note that Phalan holds a courtesy appointment in the OSUCF and Binkley is on the OSUCF’s exploratory committee.

The problems are many, but fundamentally, the “better logging” research experiment would have been appropriate in 1920s but not today. The results of this kind of research will not be applicable to most forestland owners in western Oregon and in most particular the Oregon Coast Range. Almost all of the federal public land in the Oregon Coast Range is administered as conservation reserves, where logging has totally ended or soon will. Sixty percent of Oregon’s private timberlands are owned by profit-maximizing entities that are not interested in lightening their logging to provide public goods and services. The OSUCF is proposing to explore less-damaging logging techniques when the problem is that the damaging logging is driven by Wall Street–fueled profit maximization. Less-damaging forestry cannot address absentee greed.

The “intensive” part of the OSUCF’s research regime won’t yield useful results in that it is based on sixty-year clear-cut–plant–spray–thin–spray–thin–clear-cut rotations, which is not comparable to the industry norm of forty-year rotations. When dreaming of net present value, what a difference two decades make! (For the record, I don’t favor sixty-year clear-cut rotations; I favor no clear-cutting.) OSUCF’s “research” will involve logging older forests (in this case sixty-five-plus years of age). Most standing timber on private lands in Oregon is not, and will never reach, sixty-five years of age.

Figure 9. The three kinds of “management” detailed in the draft plan. If you are a marbled murrelet, either intensive or extensive logging will kill you. Source: OSU College of Forestry.

“Working”[sic] Forests

Let’s get one thing straight right now: all forests are working forests. The term “working forest,” as used by the OSUCF in the draft proposal, is offensive. All forests “work” for society, whether they produce fiber or not. The term suggests that forests not subject to logging are not working and occupy the same ranks as welfare cheats, trustifarians, and dilettantes. Use of the term shows the fundamental bias of the OSUCF against natural forests and for wood production. But what can one expect from an institution that in 2013 set up the “Institute for Working Forest Landscapes”?

As noted in the forestry textbook Ecological Forest Management (ironically, by three authors who have had very long associations with OSU):

All forests are working forests, because they all carry out multiple functions that create a broad array of services and products valued by humans—for example, by capturing the sun’s energy through photosynthesis and using it to grow and sustain this architectural wonder that sequesters carbon, stabilizes soils, and regulates hydrological cycles, including moderating the effect of storms.

In fact, the non-raw-material ecosystem goods or services from a temperate forest are on the order of sixteen times more valuable to society than the raw material (fiber, fuel, or fodder) (Costanza et al. 2014, cited in Kerr 2019). Foresters, heal thyselves!

Map 1. The proposed macro land allocation for the ESRF, with areas of older natural forest darkened. On the ESF, if trees are over sixty-five, it’s natural forest; if they’re under sixty-five, it’s a plantation after a clear-cut. The blue-shaded area would be the Conservation Research Watersheds. The plantations (light blue) would be thinned once to help them recover on their way to becoming natural forest again, with the roads then removed. Much—but not quite all—of the older natural forest (brown) would be in reserves within the Management Research Watersheds. Source: OSU College of Forestry.

OSU College of Forestry Competence

Historically, the OSU College of Forestry has been a handmaiden to the timber industry. Much of it—but not all of it—still is. As public attitudes toward forests have changed, so too has the OSUCF. However, the college still houses the last of Oregon’s academic timber beasts. Some are unreconstructed and still advocate for short-rotation industrial “forestry” monocultures of endless Douglas-fir. The more dangerous timber beasts are the reconstructed ones, who have learned the modern doublespeak of interdisciplinary, diverse, equitable, and inclusive sustainability, but in their hearts and minds are still stump-centric foresters. To them every solution to a forest problem is logging, albeit kinder and gentler clear-cuts. A telling example is that last year, the OSUCF cut down a 420-year-old tree on the MacDonald-Dunn State Research Forest.

In its defense, the college now has on its faculty some top-notch academics in matters of forest carbon, forest science, and forest fire. All of them have been pissing off Big Timber by stating inconvenient truths: that timber plantations burn more severely and are a bigger threat to communities than real forests, that the solution to taking excess carbon out of the atmosphere is not long-lived wood products but rather long-lived forests allowed to grow naturally old, that timber plantations are biological deserts, and the like.

As far as a potential ESRF is concerned, this old guard has assiduously avoided engaging the new guard in developing the OSUCF ESRF proposal. The result is that the most relevant research questions (regarding, for example, carbon storage and sequestration) are not being acknowledged, while these production foresters are seeking once again to prove that one can have their forest and log it too. To their minds, with just the correct kind and amount of logging that only the forestry priesthood can conjure, species need not go extinct, water quality can be adequate, and recreation can be tolerable.

Since last summer there has been a new dean in town. Tom DeLuca came to the top job at the college by a career path that has avoided production forestry (and included a stint at the Wilderness Society). A soil scientist at heart and by training, DeLuca can perhaps clear out the dead wood at the OSCUF. The college’s ESRF proposal has improved significantly since he took the helm and perhaps can continue to improve.

Map 2. The area shaded dark green would be on track to become a fully natural forest again over time. The other colors to the east represent watersheds that would be managed under different intensities (intensive, extensive, and reserve, as illustrated in Figure 9). Source: OSU College of Forestry.

The Draft Plan: Still Incomplete But Very Much Worth Supporting in Concept

Portland Audubon notes “there are also significant unresolved issues that are still in process,” including these:

• The governance structure. (For the purposes of an ESRF, the OSUCF needs to be as transparent and accountable as any other state land management agency.)

• Selling carbon credits. (They must be additional and meaningful).

• A federal habitat conservation plan for several Endangered Species Act–protected species. (It should reflect the ESRF plan.)

• Funding mechanisms. (They must make it possible to administer the ESRF, conduct research, and fully decouple the ESF from the Common School Fund—all without mis-incentivizing a timber-driven “research” program.)

Map 3. Purple, magenta, and dark green good. Brownish orange and light green bad. Source: OSU College of Forestry.

My Analysis

To me, one always needs to keep in mind both the policy and the politics.

Policy

As proposed, the OSUCF proposal for an ESRF would be a large net conservation gain. It’s better than the previous mismanagement by the Oregon Department of Forestry. It needs to and can be improved, especially in—but not limited to—these areas:

• Governance. For the purposes of an ESRF, OSU needs to be as publicly accountable and transparent as are the ODF and the ODSL, including the ability for citizens to sue it for violating the law.

• Administration. The OSUCF, as now configured, is in no position to properly administer a landscape of this size and importance. It needs to bring in new talent and take out problematic staff.

• Marbled murrelets. Marbled murrelets are threatened with extinction. The OSUCF should not be in the business of killing murrelets, even in the name of research.

• Coho salmon. Coho salmon are threatened with extinction. The OSUCF should not be in the business of killing coho, even in the name of research.

• Northern spotted owls. Northern spotted owls are threatened with extinction. The OSUCF should not be in the business of killing northern spotted owls, even in the name of research.

• Natural forests. Especially in the Oregon Coast Range, natural forests are rare. The OSUCF should not be in the business of logging natural forests, even in the name of research.

• Conservation versus research. Conservation and research should be co-equal purposes for an ESRF.

• Research focus. The OSUCF should reconsider its emphasis on “share and spare” research and increase its focus on increasing carbon storage and sequestration in previously logged forests (plantations), making such “forests” less damaging to wildlife, water quality, scenery, and recreation.

• Endowment. The OSUCF needs an endowment so it is not reliant on timber sale receipts to fund operations and research on an ESRF.

Politics

Permit me to analyze the politics by answering in question form some comments I’ve heard from some Oregon conservationists.

Knowing of the OSU College of Forestry’s gross mismanagement of their current state research forests, how could you even think of letting the OSU College of Forestry anywhere near the Elliott?

If the OSUCF were to get its hands on the ESF, it would come with a raft of terms and conditions by the State Land Board and the Oregon legislature that can provide adequate sideboards to limit the OSUCF’s ability to screw up. Despite my recitations of the horrors of the OSUCF, and based on my relatively close and continuous observation of the college since I dropped out of OSU in 1976 (back then it was a mere “school”), the OSUCF is, by fits and starts, slowly but surely becoming a better institution. Most change comes with funerals or retirements, and I have faith in the new dean and an evolving faculty to make things significantly better over time.

The original impetus to save the Elliott was to get it out from under the Common School Fund mandate to maximize revenues for education. As the Oregon Supreme Court recently ruled that a constitutional mandate of revenue maximization did not exist, why is “decoupling” still important?

The Supremes did say that the State Land Board didn’t have to maximize timber receipts for education, but it didn’t say it could not if it wanted to. Elections happen. Teachers, administrators, and school board members will continue to agitate for ESF logging, as any money from logging is money that doesn’t have to come from the General Fund to educate children. Politically, the need to free the Elliott from the Common School Fund is undiminished.

Why can’t the Elliott just stay with the Oregon Department of State Lands?

The ODSL doesn’t want to keep the ESF, and frankly neither do the State Land Board members. The ODSL is a bad land manager, and the SLB considers it a headache.

Why can’t the Elliott just be a giant nature preserve?

In your (and my) dreams. However, there are other constituencies with interests in the Elliott, including, but not limited to: schools, Big Timber, Tribes, and recreationists. To successfully decouple the ESF from the CSF, there needs to be a broad and deep enough coalition to persuade the Oregon legislature to come up with ~$121 million to fully and finally get the Elliott out of the Common School Fund.

My Recommendations to the State Land Board

First, I’ll be thanking most members of the State Land Board for their leadership on this issue. Thanks to both Governor Kate Brown and State Treasurer Read for coming around on the issue and stepping up to lead. Read, in particular, came up with the idea of an ESRF, when there were not any other ideas. (And a shout-out, for what it may be worth, to the late secretary of state Dennis Richardson, who as a Republican joined Democrats Brown and Read to declare their intent to keep the ESF public.) As for the present secretary of state, Bev Clarno (R), I’m pleased that Shemia Fagan (D) will be the new secretary of state starting in early 2021.

Second, I’ll be strongly urging the SLB members to vote to have the ODSL proceed with further exploration of an Elliott State Research Forest. By that I mean, for example, directing that the details would include a reversionary clause where an ESRF would revert back to the ODSL in the event of OSUCF violations of the terms of the transfer, including complying with the forest management plan.

Third, I will be urging the SLB to encourage the OSUCF to finalize a plan that (again, generally according to Portland Audubon) does these things:

• Requires strong mechanisms to ensure accountability, transparency, and enforceability of the plan, including notice and comment, public records, and establishing a public right to enforce the agreements through third party litigation.

• Places a higher priority on utilizing the forest for carbon storage, carbon sequestration, climate and carbon research, and climate resilient forest management.

• Has the final plan be matched with an Endangered Species Act habitat conservation plan.

• Continues to involve stakeholders in the finalization of an ESRF.

It will take a few years to line everything up before the SLB is ready to vote for permanent transfer. The OSUCF will have finalized a forest management plan so the public knows clearly what will and will not happen on the Elliott. I’m confident that the SLB final vote on the establishment of an ESRF will be in the public interest and for the benefit of this and future generations of Oregonians. If that doesn’t happen, that bridge can be burned when we come to it.

My Last Thoughts

This is a mini version of the dilemma I faced in 1993 when deciding whether to support or oppose President Clinton proceeding with what became the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP) of 1995. Then and now, my brain has its ecological half and its political half. My political brain told me the NWFP could be a huge gain for conservation of far more than we could have dreamed of a few years previously. Yet my ecological brain told me it would not be enough conservation and restoration. My political brain won the argument by concluding it was better to take the victory then (and have a hell of a party!) and regroup afterwards to seek more improvements later. History, I believe, has turned out to support that decision.

The acreage conservation-exploitation ratio in the proposed ESRF is comparable to that of the NWFP (2:1), with the major difference being that the former calls logging “experiments” while the latter called it “logging.” In comparison, a draft habitat conservation plan for western Oregon state forests administered by the Oregon Department of Forestry is at a bit less than a 1:1 ratio.

Of course, history doesn’t often repeat itself, but it does often rhyme. Only time will tell. For now, I choose to not let the theoretically perfect be the enemy of the practically pretty good.

Let Your Voice Be Heard

The OSUCF ESRF proposal is out for public review right now. You can send a comment via website or via an email to Ali.R.Hansen@dsl.state.or.us. Please feel free to crib off my recommendations above, and get your comments in by 5 PM on November 29.

Figure 10. The West Fork Millicoma, home to fall chinook salmon, coho salmon, Pacific lamprey, winter steelhead, and coastal cutthroat trout, as it flows through the Elliott State Forest. Source: Francis Eatherington.