As shown in Map 1, there are three subspecies of sea otter:

• northern, also called Alaskan (Enhydra lutris kenyoni)

• common, also called Asian or Russian (E. l. lutris)

• southern, also called Californian (E. l. nereis)

The remote coastline of California sheltered small southern sea otter colonies from the fur trade. Fifty that survived from the original estimated 16,000 individuals were rediscovered in 1938, and that population has grown to nearly 3,000.

After 59 Alaskan sea otters were relocated from the Aleutian Islands to Washington’s Olympic Peninsula in 1969 and 1970, that restored population declined to somewhere between 10 and 43 individuals before climbing to 208 in 1989. In 2017, more than 2,000 individuals were estimated in an expanded range—still a fraction of the original range.

The population of northern sea otters is also growing in British Columbia after their reintroduction to the west coast of Vancouver Island. There are currently between 65,000 and 78,000 northern sea otters in Alaska, Washington, and British Columbia combined.

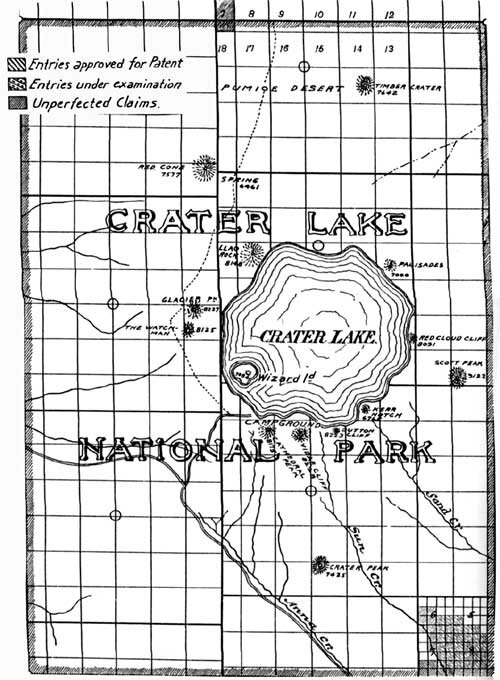

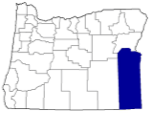

A relocation effort was also made in Oregon. According to the Elakha Alliance, in July 1970, 29 northern sea otters were relocated from Amchitka Island in the Aleutians to Redfish Rocks, and a year later 24 animals were relocated to near Port Orford (both in Curry County). In July 1971, 40 animals were also released at Cape Arago (Coos County). While pups were observed, the entire population had declined dramatically by 1975 and were gone by 1981 for reasons not well understood.

Wikipedia sums up the failed reintroduction effort and then reports:

In 2004, a male sea otter took up residence at Simpson Reef off of Cape Arago for six months. This male is thought to have originated from a colony in Washington, but disappeared after a coastal storm. On 18 February 2009, a male sea otter was spotted in Depoe Bay off the Oregon Coast. It could have traveled to the state from either California or Washington. [citations omitted]

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature notes that population estimates for sea otters from 2004 to 2012 add up to a worldwide population of 125,831. This means that from 42 percent to 84 percent of the original population still survives. Hell, a lot of species are far worse off—but globally (meaning in the northern Pacific Ocean), the species continues to decline and the populations are limited to small pockets.

In fact, under the Endangered Species Act, the southern sea otter is listed as threatened throughout its range (California, Oregon, and Washington), while the northern sea otter is listed as threatened throughout most, but not all, of its range (Alaska, and historically, British Columbia and Washington). Though presently absent, the sea otter is also listed as an endangered species under the Oregon Endangered Species Act.

Threats to the sea otter now include offshore oil and gas exploitation, local officials in Alaska wanting to put a bounty on sea otter pelts to protect shell fisheries, legal and illegal harvest of otters, fishing and harvesting aquatic resources (especially crab), recreational activities, oil pollution (oil coating the fur destroys its protective layer, resulting in hypothermia; as the otter attempts to clean its coat, it ingests large amounts of oil), urban runoff, and sewage outfall. Another threat is the climate catastrophe, as warming ocean waters and increased acidification can affect the health of kelp forests and the shellfish that otters eat, as well as promoting the spread of toxic algae that cause paralytic shellfish poisoning.

Which Subspecies to Reintroduce?

Given the earlier failure of reintroduction efforts, Oregon sea otter aficionados are proceeding carefully. One important question is: Just where was the demarcation line between the northern sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) and the southern subspecies (E. l. nereis)? Which subspecies was offshore Oregon? Perhaps both? Because northern sea otters far outnumber southern sea otters, moving otters south to Oregon would have less impact than moving them north to the state, but there is some evidence that southern sea otters might be better matched genetically to historical stocks in Oregon.

A 2007 research paper published in Conservation Genetics examined the genotypes of sixteen sea otters that lived before the slaughter commenced and whose bones were housed in the Archaeology Department at Oregon State University, and found that the “genotypic composition of pre-harvest otter populations appears to match best with those of contemporary populations from California and not from Alaska, where reintroduction stocks are typically derived.”

However, “More recent DNA and morphological analysis of bones in Oregon middens shows characteristics of both,” says Bob Bailey, a board member of the Elakha Alliance. “Geneticists now do not think there is any meaningful difference in terms of translocation.” Bailey further reports: “No decision has been made about source stock. We are about to embark on a feasibility study that should help us figure this out, but it is going to take a couple of years. The principal investigator for the study is a semi-retired sea otter scientist with forty years of experience.”

Controversy Expected

Bringing the elakha back to Oregon will be controversial, judging by past conservation efforts, especially related to species harvested for human consumption. The Elakha Alliance sums it up well:

If experience in other Pacific coast areas is a guide, the return of sea otters to the Oregon coast will likely have a mix of economic and social impacts depending on the location of their return and the number of otters. But in time, sea otters would likely have a profound impact on the diversity and productivity of Oregon’s nearshore ecosystem that, in turn, would result in an overall benefit to commercial and recreational fisheries that rely on a healthy marine ecosystem.

If they return to one or more estuaries, sea otters would likely increase water quality, reduce the presence of the invasive green crab, and promote the growth of eelgrass. Sea otters would also likely be a draw for outdoor enthusiasts and recreationists as they are in California and Alaska, and be a symbol of pride in some communities. In the long run, a robust population of sea otters would likely result in an increase in kelp beds, which would capture and store carbon dioxide, a leading cause of ocean acidification.

However, a growing population of sea otters in some areas could disrupt existing patterns of catch and consumption by some ocean users; such as sea urchin harvesters, commercial and recreational crabbers, and other harvesters of shellfish. Such competition and conflict between sea otters and humans is present today in several locations in southeast Alaska where the number of sea otters is in the thousands. But because sea otters do not readily migrate, have small home ranges, and have only one pup per year, their population growth and geographic spread will be slow. So it will be important to identify and anticipate such potential conflicts and choose release sites to minimize chances of conflict with other uses.

Putting Your Money Where Your Heart Is

If you want to know more, you may enjoy reading Return of the Sea Otter: The Story of the Animal That Evaded Extinction on the Pacific Coast by Todd McLeish.

Two conservation organizations focus exclusively on the sea otter. The Elaka Alliance focuses exclusively on returning sea otters to Oregon.

• Friends of the Sea Otter — “Friends of the Sea Otter (FSO) is an advocacy group, founded in 1968, dedicated to actively working with state and federal agencies and other groups to maintain, increase and broaden the current protections for the sea otter, a species currently protected by state and federal laws, and with two geographic populations on the Endangered Species list. We wish to inspire the public at large about the otters’ unique behavior, habitat, and to take action to recover this remarkable species.”

• Elakha Alliance—“The Elakha Alliance is an Oregon-based nonprofit organization dedicated to restoring sea otters and the health of Oregon’s nearshore marine ecosystem. Named for the Chinook Indian word for sea otter, the Elakha Alliance brings together coastal Indian tribes, conservation organizations, academic institutions, community groups, individuals, and others interested in sea otter conservation and coastal ecology.”

Send one or both organizations money. I just made a tax-deductible donation to the Elakha Alliance because they are Oregon-centric and I know and have high confidence in several members of their board of directors.