The climate, the oceans, species, watersheds, ecosystems, landscapes, cultures, and economies that depend on federal public lands all depend upon the 45th president of the United States having a bold public lands conservation agenda.

While the Property Clause (Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2) of the United States Constitution vests the power over federal public lands with Congress, as the legislative branch Congress cannot be expected to oversee the day-to-day operation of the federal public lands. Therefore, Congress has broadly set policies and then directed specified entities in the executive branch to carry them out. For example, the vast number of congressional statutes pertaining to the National Forest System make reference to the secretary of agriculture (or in some cases the chief of the Forest Service) as the responsible official empowered and directed by Congress to carry out the statute. As most federal public lands are under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior, the secretary of the interior (and occasionally the director of the Bureau of Land Management, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, and so on) is similarly empowered or directed.

Though these cabinet officers or agency heads are appointed by the president, they must be confirmed by the Senate before they can assume the office. When it comes to federal public lands, these public land officials have two masters, the president who gave them their job and the Congress—in particular the committees of jurisdiction (the House of Representatives’ Committee on Natural Resources and the Senate’s Committee on Energy and Natural Resources)—who gave them their marching orders.

In some cases, Congress has granted the president certain powers over federal public lands, most notably to proclaim national monuments or to allow or disallow the development of offshore oil and gas. The president and her cabinet and agency heads should use these and other powers granted to them by Congress to advance the cause of conservation of the public lands for the benefit of this and future generations.

What follows is a public lands conservation agenda that the next president could implement without any additional Acts of Congress. It’s unfortunate to have to assume Congress missing in action when it comes to the conservation of federal public lands, but it is. (I hear Congress was more dysfunctional just before the Civil War, but I wasn’t there.)

1. Keep it in the ground.

Federal public lands account for about a quarter of all U.S. fossil fuel production and therefore one-quarter of the carbon dioxide pollution from those sources. To help avert the worst effects of climate change, an immediate ban on new federal fossil fuel leases should be imposed, nonproducing current leases should be allowed to expire, and existing producing leases should be bought back. Doing such will not only help mitigate climate change, it will also prevent harm to the nature that depends on federal public land. Several conservation organizations, including the Center for Biological Diversity, are leading the Keep It in the Ground campaign for federal public lands.

2. Ban renewable energy development on federal public lands.

While less damaging to the climate, the supposed “green” electrons that come from renewable energy projects on federal public lands are better thought of as “light brown” electrons. Concentrated production of renewable energy from wind, solar, and geothermal is as damaging to nature as concentrated production of nonrenewable energy from coal, oil, and gas. Poxing the federal public lands with wind towers or covering them with photovoltaic panels renders that public land parcel worthless for conservation. Public lands have a higher and better use than industrial sites for any kind of energy development. For example, both the desert tortoise and photovoltaic panels find suitable habitat in the California desert. However, solar panels can live—better actually—on roofs in town, while the desert tortoise cannot.

3. Double the National Wildlife Refuge System.

Under existing congressional authorities, the secretary of the interior by secretarial order or the president by executive order can establish new or expand existing national wildlife refuges. These expansions can come from federal public lands currently administered by the Bureau of Land Management or encompass an area of nonfederal land so that the lands can later be acquired by donation or purchase from willing sellers.

4. Proclaim more national monuments.

In the Antiquities Act of 1906, Congress gave the president authority to proclaim national monuments. Hundreds of millions of acres of federal public lands in the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone and many tens of millions of acres of onshore public lands are worthy of national monument designation. Most presidents have mostly proclaimed national monuments as they were leaving office; but given the general dysfunction of Congress, national monuments should be proposed and proclaimed early and often. For some onshore areas, it may be appropriate for the president to announce her intention to proclaim a national monument well in advance in order to spur Congress to act to conserve an area in ways that can be superior to a national monument proclamation. For example, President Obama’s interest in proclaiming a national monument in Idaho in 2015 prompted Congress to establish 275,000 acres of wilderness in central Idaho—a bill that had been languishing for nearly a decade.

5. Save Wyoming and Alaska federal public lands in other creative ways.

Part of the 1950 congressional deal to combine Grand Teton National Monument (est. 1929) and Jackson Hole National Monument (est. 1942) to create Grand Teton National Park excluded Wyoming from any future presidential proclamations of national monuments. In Alaska, since enactment of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, the president’s authority to proclaim new national monuments is limited to ones less than 5,000 acres in size. Much of the 73 million acres of BLM holdings in Alaska and the 18 million in Wyoming are in need of elevated conservation. With the Antiquities Act rendered useless in these two states, the president could establish new national wildlife refuges or direct her secretary of the interior to do so. In addition, the president could issue executive orders directing the BLM to manage particular areas of public lands for conservation purposes and to prohibit harmful activities.

6. Keep it in the forest.

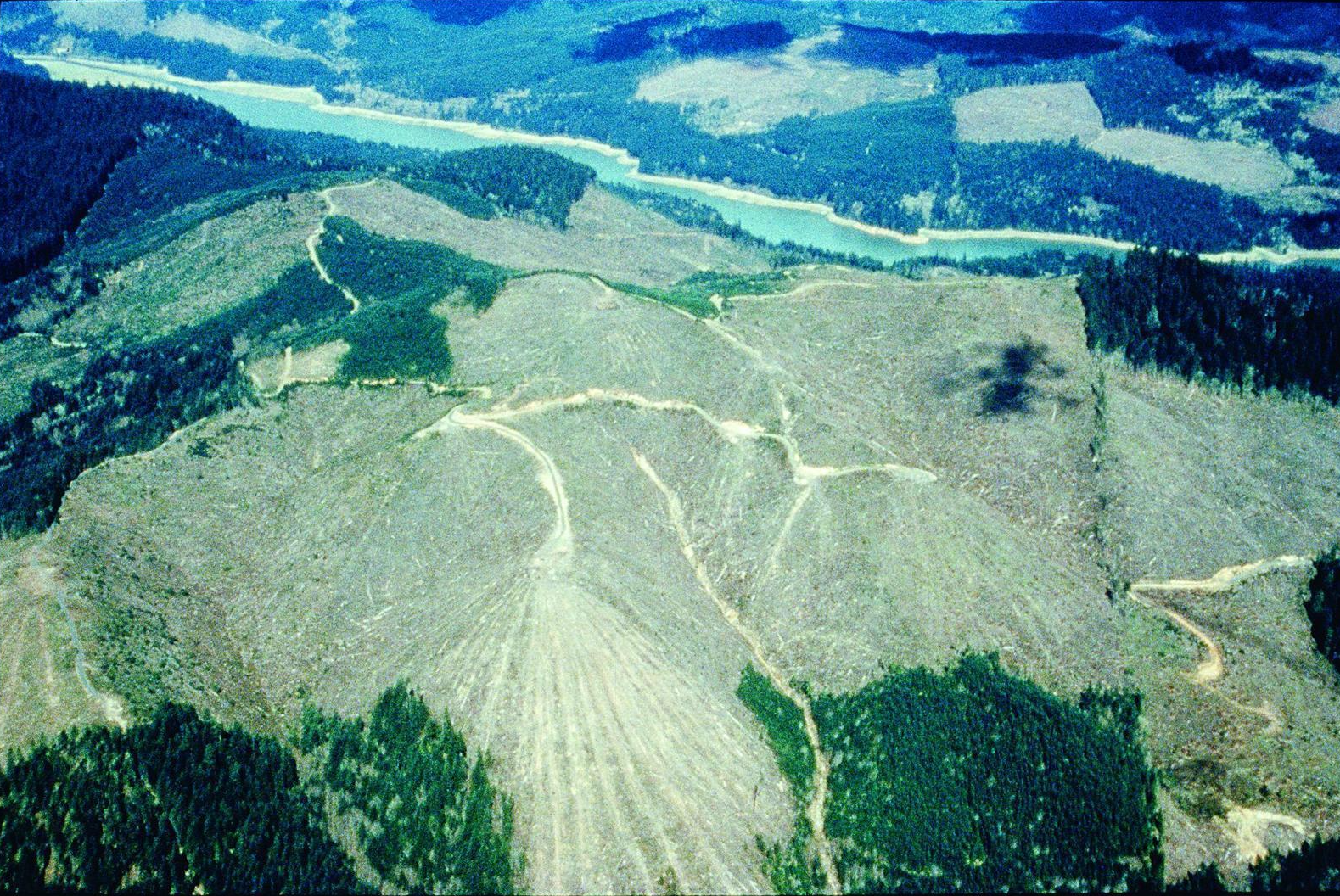

A very large fraction of the excess atmospheric carbon came not from the burning of fossil fuels but from the conversion of native forests to cities, farmlands, and clear-cuts. Forests on federal public lands need to be protected in order to remove excess carbon from the atmosphere and store it securely.

The United States owns tens of millions of acres of “moist” (not subject to frequent fire) forest types in southeastern Alaska, western Washington, western Oregon, northern California, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana. These moist forests act as huge and secure stores of carbon, and they also sequester additional carbon back to the biosphere from the atmosphere. Most are within the National Forest System, but some significant areas are administered by the BLM. By executive order, the president could direct the secretaries of agriculture (Forest Service) and interior (BLM) to set aside “carbon reserves” that contain moist forests to conserve already-stored carbon and to maximally sequester additional carbon to help ameliorate the effects of climate change. Many of these moist forest stands consist of older (mature and old-growth) trees that are best suited to resist and adapt to climate change.

7.Keep it in the grass.

Temperate grasslands store more carbon on average than temperate forests, according to a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The difference is that most of the carbon in a forest is aboveground, while most of the carbon in a grassland is belowground. Livestock grazing and other destructive agricultural practices have not only severely reduced aboveground carbon stores (otherwise known as plants) but also allowed the release of much belowground carbon. Carbon reserves such as those recommended for moist forest types could also be established to protect public land deserts and grasslands.

8. Raise royalties on federal energy revenues.

While the best thing for the world’s climate is for the federal government to collect no royalties from fossil fuel production on federal public lands as it should no longer be allowed, until that time the taxpayers should receive a fair return on something private entities are allowed to sell. A report by the Center for Western Priorities notes that the royalty paid to the federal treasury for fossil fuel production from federal lands is 12.5 percent of revenues. Compare this to the 16.75 percent charged by Wyoming, Utah, Montana, and Colorado, or the 18.75 percent charged by New Mexico and North Dakota, or the 25 percent charged by Texas for fossil fuel production from state lands. The federal government receives 18.75 percent for offshore oil and gas.

Besides representing a fair percentage of revenues, the royalty should factor in the social cost of carbon (SC-CO2). SC-CO2 is measured in $/tonne and includes—but is not limited to—the cost of changes in net agricultural productivity, adverse impacts on human health, property damage from flooding, and changes in the energy system due to climate change. It is the cost to society of placing CO2 in the atmosphere. Burning a barrel of oil (42 U.S. gallons) emits 0.43 tonnes of CO2. West Texas Intermediate (WTI Crude Oil, a benchmark for oil prices) is trading for around $50/barrel. Ifthe SC-CO2 is $36/tonne CO2, adding the social cost of carbon to the price of a federal barrel of oil would increase its price by ~$16. It probably wouldn’t offset the special tax breaks afforded to fossil fuel producers that are permanently embedded in the U.S. tax code, but it would help level the playing field for sustainable and renewable forms of energy.

9. Withdraw all scenic- and recreation-classified wild and scenic rivers from mining.

In its wisdom (pronounced “compromise”), Congress specified in the 1968 Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA) that only the segments of wild and scenic rivers classified as “wild” would be withdrawn from the application of the federal mining laws. Those segments classified as “scenic” or “recreational” are not protected by WSRA from mining. The difference is that a “wild” segment generally has no roads in its corridor, whereas a “scenic” segment may have a road crossing its corridor and a “recreational” segment a road along its corridor. If a stream is worthy of inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSRS), it’s worthy of not being mined. Some—but far from all—such stream segments have been withdrawn from mining by the secretary of the interior under the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act withdrawal provision for the maximum allowed twenty years. All of the NWSRS should be so protected from mining.

10. Link mineral withdrawals to management plans.

The Forest Service and the BLM develop land and resource management plans under the authority of the National Forest Management Act and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), respectively. In such plans the agencies designate lands for conservation and sometimes prohibit such things as logging, road building, grazing, off-road vehicles, fluid mineral leasing, and other activities that would harm the values for which the area is being managed. However, under the Mining Law of 1872, an area of federal land may only be protected from hardrock (gold, etc.) mining if the area has been “withdrawn” pursuant to the withdrawal provision of FLPMA. The president should direct the BLM and the Forest Service to promptly apply to the secretary of the interior for such mineral withdrawals, and she should direct the secretary to promptly withdraw them.