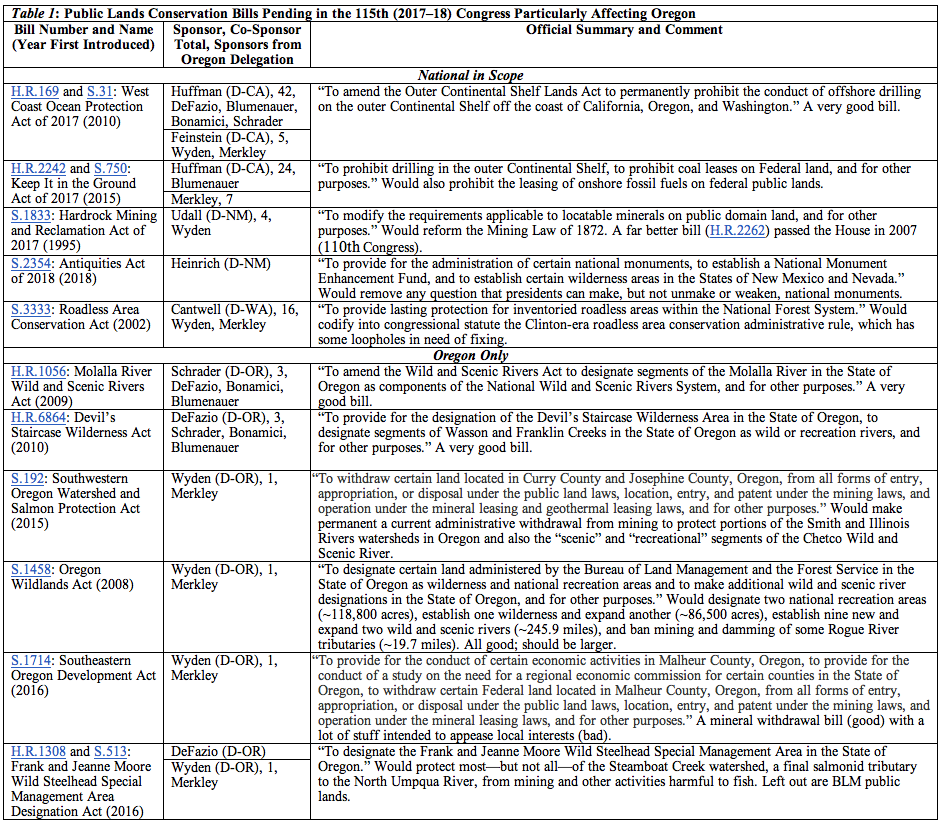

Several mostly good public lands conservation bills have been introduced in the 115th Congress (2017–18) but languish in committee, unable to get a vote on the floor of the House or the Senate (Table 1). For the most part, these bills are popular and uncontroversial, and when they do get to the floor they will pass. When that happens and the congressional pipeline finally does unclog, conservationists need to make sure that pipeline is full.

Priority: Saving older Douglas-ir (and all other) forests for this and future generations. Photo: Gary Braasch (first appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness (2004 Timber Press)

The Clog

As noted in Table 1, some have been introduced into several previous congresses (the two-year period between elections). None are going anywhere right now.

The problem is that the Republican leadership in both houses is anti–public lands conservation. Two major reasons (examined in more detail in the Public Lands Blog post “Public Lands Conservation in Congress: Stalled by the Extinction of Green Republicans”) account for this:

• The Republican Caucus in each house has members, mainly from the Mountain Time Zone, to whom public lands exploitation is very important if they are to get reelected (not so much for the votes as for the campaign money).

• Most public lands conservation bills are sponsored by Democrats, and the Republican leadership is loath to give their opponents any kind of a win, even though a public lands conservation win would be good for the people.

It’s so bad that even when the occasional Republican has a good public lands conservation bill pending, that bill doesn’t move either.

There is a difference between a clog and a slog. In a clogged pipeline, very few, if any, bills move forward. A slog refers to a piece of legislation, often complex and always controversial, that has a long way to go before it is finally enacted into law. A clog extends a slog. An example of a slog bill is reform of the Mining Law of 1872 (yep, that’s right), in which the modern reform effort began in 1995).

An Exhortation: Take the Long View and Play the Long Game

When being shelled in a foxhole, it is difficult to consider moving forward, but that is the most important time to do so. To those who say “the politics just aren’t right,” I say they never are until they are. When they are, conservationists and their congressional allies must be ready. Success in public lands conservation, either by presidential proclamation or by congressional action, is always a result of the alignment of the political stars. While some of the necessary stars will line up due to forces outside our control, many can only be aligned by effective and tireless advocacy.

Achieving great conservation victories often takes a long time—but not always. Consider these examples:

• William Gladstone Steel and the Mazamas outdoor group (still going strong) advocated for a Crater Lake National Park for more than three decades before Congress established it in 1902.

• More than two decades elapsed from when the Forest Service removed the French Pete Valley from the Three Sisters Wilderness in 1957 to when Congress put it back in 1978. The Sierra Club and others were on the case every step of the way.

• Conservationists first advocated for the Middle Santiam Wilderness (within the proposed national monument) in the mid 1970s. It had the most board feet per acre (a timberman’s way of measuring old-growth forest) of any Forest Service roadless area in the country. All but one member of the Oregon congressional delegation (Rep. Jim Weaver, D-4th) was afraid of saving the Middle Santiam. Conservationists caught a break when Jimmy Carter became president in 1976 and supported it for wilderness. Though Carter lost in 1980, the momentum generated by the Middle Santiam Wilderness Committee and others resulted in Congress protecting it in 1984.

• The National Park Service first proposed expanding Oregon Caves National Monument in 1938 by including land from the adjacent Siskiyou National Forest. The Forest Service and the timber industry were both very hostile to the idea. Finally, prodded by the Klamath-Siskiyou Wildands Center and others, in 2014 Congress nonupled (increased by nine times) the protected area. (That’s seventy-eight years total for those who are counting.)

• The Soda Mountain Wilderness Committee worked for more than three decades to get Congress to establish the Soda Mountain Wilderness. Along the way, the committee also secured significant levels of administrative protection and a national monument that surrounds the wilderness.

• The Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 established the Cummins Creek, Rock Creek, Drift Creek, Black Canyon, Bridge Creek, North Fork John Day, Mill Creek, Waldo Lake, Monument Rock, Table Rock, and Menagerie Wildernesses. Spearheaded by Oregon Wild, advocacy for the protection of these areas by Congress began in 1979 at the earliest and 1981 at the latest. Sometimes the stars can align relatively quickly. Need met opportunity, and the local advocates were ready.

• In 2000, Congress enacted the Steens Mountain Act, which protected 1.1 million acres from mining and 0.5 million acres from off-road vehicles and other harms, and established 175,000 acres of wilderness, with 100,000 of that being the nation’s first livestock-free wilderness. The Audubon Society of Portland, the Oregon Natural Desert Association, the Sierra Club, and the Wilderness Society were all ready to seize that opportunity because they had organized popular support even before the opportunity arose by President Clinton (through Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt) threatening a national monument if Congress did not act within the year.

Some of Oregon’s greatest public lands conservation achievements took one or multiple decades—one even a lifetime. Others happened in half a decade. All, save for Oregon Caves, resulted from the constant sustained effort of conservation activists whose love of the place and the threats to that place meant they had no choice but to try. All started as what Henry David Thoreau called castles in the air: “If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.” Said foundations were put.

Older Sitka spruce in the Oregon Coast Range. Photo: Gary Braasch (first appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness (2004 Timber Press)

Some More Things to Put in the Pipeline

At some point, the congressional pipeline will unclog and public lands conservation bills will pass into law. Conservationists need to make sure the pipeline is full when it does finally unclog. Here’s a partial, off-the-top-of-my-head, shopping list:

• Establish an offshore Oregon and Washington national marine sanctuary or marine national monument, or protect the coast in some other way.

• Establish, by act of Congress or presidential proclamation, additional national monuments, including but not limited to Fort Rock Lava Beds, Diamond Craters, Jordan Craters, Owyhee Canyonlands and the Douglas-Fir National Monument.

• Expand the Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge so it abuts the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge.

• Establish numerous new and expand several existing Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management wilderness areas.

• Expand the Oregon Coast, Upper Klamath, and Malheur National Wildlife Refuges.

• Establish the New River, Boardman Grasslands, and Lake Abert National Wildlife Refuges, and others.

• Establish the Illinois Valley National Salmon and Botanical Area.

• Establish several new national recreation areas (the ranger districts of the 21st century) that overlay an underlay of wilderness and wild and scenic rivers, and expand existing ones.

• Change the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to prevent mining on public lands in those wild and scenic river segments designated as “scenic” or “recreational.”

• Enact comprehensive voluntary federal grazing permit retirement legislation.

• Protect all older (mature and old-growth) forest stands and trees on all federal public lands in Oregon.

• Establish and expand several wild and scenic rivers.

• Expand Crater Lake National Park.

• Establish the Steens-Alvord National Park Preserve.

• Transfer the Oregon Redwoods to the National Park System.

• Establish the Elk River National Salmon Conservation Area.

• Expand the Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area.

• Provide statutory corridor protection for the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail.

• Establish the Oregon Desert National Trail, the Desert National Trail, the Pacific Coast National Scenic Trail, and others.

• Abolish the BLM and replace it with a National Desert and Grassland Service.

• Establish a National Desert and Grassland System.

• Keep all fossil fuels on public lands in the ground.

• Expand the National Forest System by (1) establishing and expanding national forests to reconvert private timberlands to public forestlands; and (2) transfer western Oregon BLM lands to the Forest Service.

• Establish several national heritage areas in Oregon.

• Round out the National Landscape Conservation System.

• Establish a National Wildlife Corridor System.

Preparing to Play Offense Again, Sooner or Later

For federal public lands conservation, no doubt about it, these are dark times. The Trump administration has the public lands conservation community on the defensive. We are having to defend the very existence of the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, the National Monuments (a.k.a. Antiquities) Act, and others, while we also seek to block the administration’s weakening of environmental protection regulations that harken back to President Nixon. But sooner or later, conservationists will get the ball back, and we must be prepared to play offense when that time comes.

Administrations change, new Congresses get elected, and congressional pendulums swing—over the decades and centuries, more toward conservation and less toward exploitation. We cannot know how long the present president will be president or exactly when the congressional pendulum will swing back toward public lands conservation. We do know that things will change, including Oregon getting a sixth seat in Congress starting with the 2022 election.

At this point, it seems probable that leadership of the House of Representatives will change to the Democrats after the 2018 midterm elections. The same is highly unlikely (but not quite impossible) for the Senate. If the House switches, we must be ready to seize the opportunities. If the Senate also switches, it’s off to the races!

Old-growth ponderosa pine near the Metolius River. Photo: Elizabeth Feryl (first appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness (2004 Timber Press)