Several federal wilderness areas in Oregon would be roaded clear-cut if not for former Representative Jim Weaver (D-4th-OR, 1975–1987). Weaver has been the greatest wilderness advocate to represent Oregon in the U.S. House of Representatives so far.

Weaver will be ninety on August 8, 2017. I have a policy to remember some Oregon public lands conservation greats before they, in words from Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be” soliloquy, “have shuffled off this mortal coil.” It is an interesting exercise and a challenge to write a remembrance of someone not yet passed. I call it a preremembrance.

James Howard Weaver was born in Brookings, South Dakota, in 1927 and ended up in Eugene in 1947 attending the University of Oregon. Before defeating incumbent Republican Representative John Dellenback in the post-Watergate 1976 election, Weaver was a developer of office and apartment buildings. Weaver served six terms in the House of Representatives, where he was known as pro-environment, anti–Vietnam War, and anti–nuclear power.

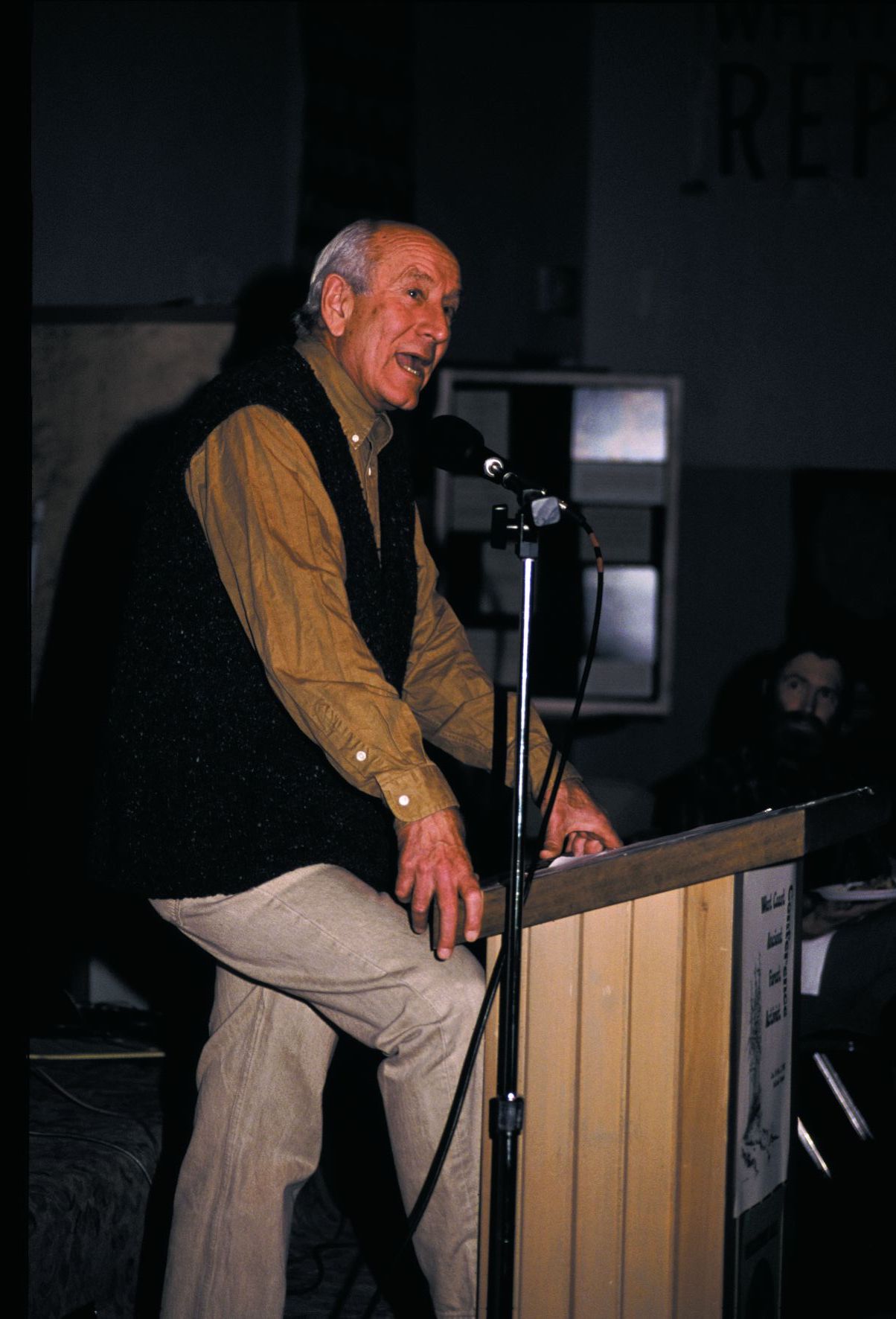

Jim Weaver, Oregon conservationists (ca early 1990s). Source: Elizabeth Feryl, Environmental Images

Passion and Paranoia

Weaver could have been a Shakespearean actor, with passion and paranoia characterizing his performance as a United States congressperson. There are generally three kinds of politicians: (1) those who have few or no principles or issues they really care about; (2) those who do have principles and issues they really care about but moderate them to get elected or gain influence inside the legislative body by getting along in the hope of furthering their principles and issues; and (3) those who have strong principles and issues and do not moderate them either for election or influence. Weaver was the third kind.

He was extremely passionate about many things and was the consummate outsider politician, seeking to change the world, more times than not, by speaking truth to power. I recall Weaver temporizing only on gun control (today it’s called gun safety), where he represented southwest Oregon. It was understandable, as I hail from there and grew up in a house with more guns than place settings.

In 1980, in attempting to kill a bill to bail out the Washington Public Power Supply System, a syndicate of nuclear power plants that resulted in the second-largest municipal bond default in U.S. history, Weaver did the only filibuster in modern House history by offering 113 amendments to the bill. Later, the House amended its rules (the “Weaver rule”) to prevent another filibuster.

Weaver knew his congressional district and what worked and didn’t work and what he could do and not do. He was more pro-environment, especially on matters of conserving public lands for this and future generations, than was his district. But he was a good populist and labor Democrat taking on the special interests, and that worked well to get him reelected.

Most incumbents after a couple of elections enter a safe zone where the opposing party fields no or nominal opposition. Weaver never had an easy race. The timber industry, big in the day, loathed him (though he split them because he opposed the export of raw logs, which some in Big Timber loved and others hated).

Weaver’s passion gene came on the same political chromosome as his paranoia gene. As a politician who never gained a safe seat, Weaver was necessarily always looking over his shoulder. (Just because you are paranoid, it doesn’t mean you are not being followed.)

Down-district (not Eugene-Springfield) media generally loathed Weaver. For example, before and during his early years in Congress, Weaver donned a toupee. He eventually doffed the rug, but the Roseburg News-Review, until Weaver left office, always used one picture of an artificially hirsute Weaver. Every time, Weaver’s media staff would send the newspaper a recent photo, but none ever made it into print.

Wilderness Bills: Taking on Hatfield

During his first two terms in Congress (1975–1978), Weaver championed what became the Endangered American Wilderness Act, which included additions to the Kalmiopsis, Mount Hood, and Three Sisters wilderness areas and established the Wild Rogue and Wenaha-Tucannon wilderness areas. The “endangered” bill was the background for this very junior member of Congress taking on the very senior Oregon Republican U.S. Senator Mark Hatfield. Weaver championed the return of French Pete, a series of low-elevation older forest watersheds, to the Three Sisters Wilderness. Hatfield had long opposed French Pete, but the political winds had changed and Hatfield finally joined with Weaver to do the right thing.

In early 1978, Hatfield’s Oregon Omnibus Wilderness Act had passed the Senate and would have added 82,400 acres to the Kalmiopsis Wilderness Area. However, as originally introduced, Hatfield’s bill would have added 134,000 acres to the Kalmiopsis Wilderness. Weaver’s own proposal was for a 134,000-acre Kalmiopsis Wilderness addition and an adjacent 136,000-acre Wilderness Study Area. Weaver then persuaded the House to include all 280,000 acres as an addition to the already protected wilderness. A heated conference committee meeting ensued, and to resolve the differences between the two bills, the final addition was set at 92,000 acres. In 1978, for the Kalmiopsis, Hatfield won and Weaver lost, though not for lack of trying.

The House staff knew the area better than the Senate staff, so the northern boundary of this new wilderness addition was drawn to prevent the planned Bald Mountain Road. When Hatfield later learned this, he introduced a rider to move the boundary so as to allow the logging road to be built. The actual construction of the road was a catalyzing event in the Pacific Northwest Timber War.

It used to be that Oregon wilderness bills were enacted into law every six years, coincidental with the re-election of Senator Hatfield: 1972, 1978, 1984, 1996 (1990 was an exception in that the northern spotted owl had hit the political fan and the Northwest Timber War had begun).

Another showdown between Weaver and Hatfield would occur in 1984. I call it a draw (no small feat for Weaver), but it resulted in the largest single wilderness package ever enacted into law for Oregon. In 1977, the Carter administration, responding to concerns about the first Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE I) raised during congressional consideration of the Endangered American Wilderness Act, ordered the Forest Service to again review de facto wilderness lands (all roadless areas larger than 5,000 acres and roadless areas of any size bordering a designated wilderness area) and make recommendations to Congress. RARE II began with good intentions but in the end was again co-opted by the timber-dominated agency. Out of the2.9 million acres reviewed in Oregon, the Forest Service recommended only 415,000 acres for wilderness protection. Another 300,000 acres were designated for further study to determine whether they should be recommended for wilderness protection. The remaining 2.3 million acres were designated non-wilderness, to be left open to roading and logging. In 1979, Senator Hatfield responded to the Forest Service’s RARE II recommendations by introducing and passing a bill that would have granted wilderness status to a mere 451,000 acres.

The Senate bill died in the House in 1980. No further congressional action was taken on Oregon wilderness protection until late 1982. Though Hatfield and Weaver agreed on numerous areas to be designated as wilderness, they vehemently disagreed about the remaining areas. The open hostility increased dramatically as their individual bills progressed through the dual chambers of Congress. While half (and the most publicly visible part) of the debate over the Oregon Wilderness Act centered on which areas to designate as protected wilderness, the other half concerned the fate of the roadless areas not to be protected.

Of all the roadless areas in the country, none had a higher volume of standing timber than the Middle Santiam. The private land to the west as totally clearcut by Weyerhaeuser and created the "green wall" of natural national forest. In 1984, Congress only designated 8,709 acres as Wilderness (we asked for 24,000 acres). The timber industry was shocked that Congress would designate a Wilderness will low-elevation old-growth forest. There are 9,219 acres of adjacent roadless old-growth forest still standing that still need to go into the National Wilderness Preservation System. Map Source: USDA Forest Service.

The timber industry favored “release” language for areas not receiving wilderness protection, which would have precluded the areas from ever being considered by the Forest Service for wilderness again, as was then required by law. Of course, conservationists opposed releasing any areas from the legal requirements that compel the Forest Service to periodically consider roadless areas for wilderness and make such recommendations to Congress.

To help frame the wilderness versus timber debate, Weaver stated he would not support a wilderness bill that affected more than 2 percent of Oregon’s timber supply. Even Weaver was surprised when Oregon conservationists complied by proposing legislation that would have established 1.9 million acres of wilderness. While affecting only 2 percent of Oregon’s timber supply, the proposal still contained too many acres and board feet for those political times.

In late 1982, to force Congress into action, the Oregon Natural Resources Council (now Oregon Wild), the National Audubon Society, and other conservation organizations threatened to file a lawsuit to prevent the further development of Oregon’s national forest roadless areas without preparation of an adequate environmental impact statement for RARE II. The state of California had recently won a similar lawsuit, so it was a slam-dunk case.

During the post-election lame duck congressional session in December 1982, Weaver used the threat of the RARE II litigation to push another wilderness bill in the House, a bill that would have designated 1,118,875 acres of wilderness and wilderness study areas in Oregon. Though it was supported by a clear majority during House consideration, it had to be brought to the floor under a “suspension of the rules.” This meant the bill as presented could not be amended and a two-thirds majority was required for passage. The bill lost with 247 yeas and 141 nays.

The bitter division among the Oregon congressional delegation continued throughout 1983. The conservation community remained split over whether to file the highly meritorious but politically problematic RARE II lawsuit. Weaver’s failed wilderness bill of the previous Congress was resurrected that current Congress as H.R.1149 and passed the House easily in March 1983—and included about 10,000 more acres. Had the Senate passed the House bill, it would have resulted in an additional 1,128,375 acres of Oregon wilderness.

While Weaver led the House effort for Oregon wilderness in the early 1980s, Representatives Les AuCoin and Ron Wyden (Oregon Democrats) also played important roles. Weaver can be credited with the 1983 House bill having as much acreage as it did, and it passed the House partly due to AuCoin’s work. That the North Fork John Day, Salmon-Huckleberry, and Badger Creek areas were as large as they were, and that Table Rock was included in the bill at all, are due to Wyden’s leadership. After passing the House, the bill went to the Senate, where it languished for the rest of 1983.

In December of that year, the long-threatened RARE II lawsuit against the Forest Service was filed. The suit successfully prevented the Reagan administration from building roads and logging in the 2.2 million acres of Oregon national forest lands recommended for non-wilderness. It also forced Hatfield to finally act on wilderness legislation. Hatfield passed a modified and diminished version of H.R.1149 totaling 780,500 acres through the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. His bill also included “soft release” of lands categorized as non-wilderness. Soft release differed from the timber industry’s hoped-for hard release by theoretically requiring future agency consideration of these lands for wilderness designation in ten to fifteen years.

Under the political threat of the litigation, the Oregon congressional delegation soon reached a compromise that added 861,500 acres of wilderness in Oregon. The Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 added the first extensive stands of Oregon old-growth forest to the National Wilderness Preservation System. In addition to Drift Creek, these included the Middle Santiam, Waldo Lake, Rock Creek, Salmon-Huckleberry, Cummins Creek, Bridge Creek, Black Canyon, Badger Creek, Bull-of-the-Woods, Boulder Creek, Mill Creek, Grassy Knob, Monument Rock, North Fork John Day, North Fork Umatilla, and Rogue-Umpqua Divide wildernesses.

The bill also designated Oregon’s first forest wilderness of less than 5,000 acres in size, the Menagerie Wilderness. The bill included Oregon’s first BLM-administered wilderness, the Table Rock Wilderness. (The Wild Rogue Wilderness also includes BLM lands but is administered by the Forest Service.)

In addition, previously unprotected stretches of the Cascade crest were finally protected in the Columbia, Mount Thielsen, and Sky Lakes wildernesses. The Diamond Peak, Mt. Jefferson, Mount Washington, and Three Sisters wildernesses along the Cascade crest were also widened to include lower elevation and more diverse forestlands, as was the Strawberry Mountain Wilderness. Finally, some more classic wilderness (small in size, high in elevation, and/or with few trees) was protected in the Red Buttes Wilderness and the Gearhart Mountain and Hells Canyon wilderness additions.

Thanks, Jim!

In 1986, Weaver challenged Oregon Republican U.S. Senator Bob Packwood, who was seeking re-election. The House Ethics Committee probed Weaver’s campaign finances, and Weaver dropped out of the election in August. Later, the House Ethics Committee stated Weaver had not violated the law and that the earlier filings contained errors.

As Jim Weaver quietly lives out his days in his beloved Oregon, this and future generations are in his debt because even though he represented the congressional district ranked highest for timber production in the nation, Weaver was a strong and tireless proponent of wilderness. There are wilderness areas today safely on the map, both inside and beyond his congressional district, because Jim Weaver stood up for the wild in Oregon in ways that no elected official had done before or has done since.

Thanks, Jim!

(A more comprehensive retelling of Oregon wilderness political history, including pre- and post-Weaver, is found in Chapter 3 of my book Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness.)