Trigger warning for wilderness purists: I’m going to argue that mountain bikes in wilderness areas are not a unqualified evil and in fact—if wilderness advocates are visionary, strategic, pragmatic and relevant—can be a qualified opportunity.

The Political Challenge of a New Technology

In my father’s day, the preferred method of accessing wilderness was pack stock, mainly horses. Cooking utensils, food, tents, sleeping bags, and other gear were heavy. Those who walked into wilderness were reliant on the legendarily infamous Trapper Nelson pack frame that precluded the need for pack stock but limited the distance one could travel in wilderness.

In my day (I’m sixty-two, the preferred method of accessing wilderness was backpacking, aided by massive improvement in gear quality (better and lighter, with emphasis on the latter).

Today, an increasingly preferred method of accessing the backcountry is via mountain bike. The first production mountain bike went on sale in 1979. The concept was simple: a tough bike for backcountry use on rough routes, such as on public lands. Now, relatively speaking, mountain biking is on the rise, pedestrian use is stable at best, and equestrian use continues to decline. The next time you visit your REI store, consider the amount of floor space allocated to mountain bikes versus backpacking gear. I’m pretty sure REI never sold horse tack, but they would if there were the demand.

Most mountain bikers love wilderness at least as much as they love their mountain bikes, so they have gravitated to roadless areas (de facto wilderness, as their form of mechanized transport is officially banned in wilderness areas. And thus the stage has been set for political conflict between mountain bikers and wilderness advocates.

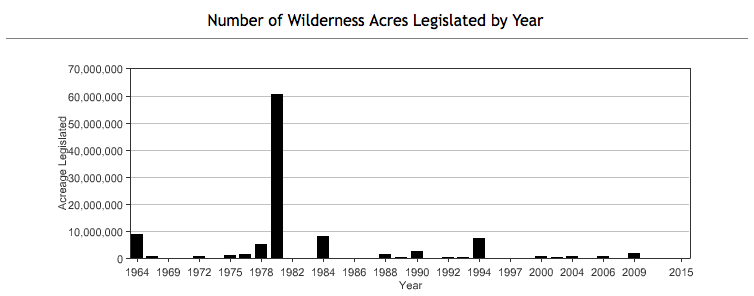

The year 1984 saw the single greatest expansion in the number of wilderness areas ever (see table). Mountain bike conflicts in roadless areas being proposed for wilderness were not even an issue that year. But in subsequent decades, mountain bike conflicts have come to the fore. Mountain bikers have politically colonized Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management roadless areas that are wilderness in fact if not (yet) in law. Today, as wilderness advocates seek to include additional roadless areas in the wilderness system, they are often running up against mountain bikers who have established use in these roadless areas.

Source: www.wilderness.net

In fact, the mountain biking community increasingly poses one of the greatest political challenges to the designation of additional wilderness areas. Yes, timber, mining, livestock, and off-road-vehicle interests always oppose wilderness. While mountain bikers generally want to save de facto wilderness areas from such exploitation, they also want to enjoy mountain biking in those areas.

Wilderness advocates have generally adopted a policy of accommodation with mountain biking interests, and vice versa. For example, we very likely could have had another ~28,300 acres of new wilderness acreage on the Mount Hood National Forest in 2009 had it not been for mountain biking conflicts. Boundaries were moved and areas were dropped to accommodate mountain biking use. For ~12,500 of those acres, other congressional conservation designations afforded protection against mining, logging, roading, and such. Another ~15,800 acres were afforded no congressional protection.

I once asked a prominent wilderness advocate in California if he was concerned about mountain biking conflicts politically precluding wilderness designation. I was perplexed when he said no. Then he explained. In essence the current supply of roadless lands in California that qualify for wilderness designation is far larger than the political demand (as expressed by legislation being introduced) for more established wilderness areas. So wilderness advocates simply throw the mountain bike–conflicted roadless areas over the side and focus on roadless lands without mountain bike conflicts.

Legislation to Open Up Wilderness to Mountain Bikes

Legislation has been introduced in the current Congress to amend the Wilderness Act to allow mountain bikes (and other wheeled devices) in the National Wilderness Preservation System. H.R.1349 is only one short paragraph:

Section 4(c) of the Wilderness Act (16 U.S.C. 1133(c)) is amended by adding at the end the following: “Nothing in this section shall prohibit the use of motorized wheelchairs, non-motorized wheelchairs, non-motorized bicycles, strollers, wheelbarrows, survey wheels, measuring wheels, or game carts within any wilderness area.”

This legislation’s chief sponsor is Representative Tom McClintock (R-4th-CA). Cosponsors include Republican Representatives Duncan Hunter (R-50th-CA), Bruce Westerman (R-4th-AR), Stevan Pearce (R-2nd-NM), Kevin Cramer (R-at large-ND), and Dana Rohrabacher (R-48th-CA). The lifetime League of Conservation Voters scores for this despicable cast of characters are 4 percent, 2 percent, 1 percent, 4 percent, 1 percent, and 10 percent, respectively. (Westerman is the chief sponsor of legislation that is an existential threat to public lands.) The majority of sponsors hail from California, where the mountain bike was invented and has reproduced prolifically.

The inclusion of wheelchairs is intended to gain sympathy for the bill and cast wilderness advocates as anti-access for less-than-fully-abled people. In fact, wheelchairs are allowed in wilderness areas already, so this provision is unnecessary insofar as wheelchairs.

“Strollers” is a new gambit, but almost any parent wanting to take their child into the wilderness would find that strapping the stroller-sized child to their body with one of the many available devices for just that is a far more enjoyable experience.

I once help haul a large dead elk out of what is now the Monument Rock Wilderness. We didn’t need no stinking game cart or wheelbarrow, only friends, knives, saws, plastic bags and pack frames. As for survey wheels and measuring wheels, which are mechanical devices to measure distance, they are not “mechanized transport,” which the Wilderness Act prohibits, so those are another bullshit gambit.

It’s all about mountain bikes.

McClintock’s bill is championed by the Sustainable Trails Coalition, a Colorado-based nonprofit steered by a board composed of avid outdoorspeople, all of whom enjoy mountain biking.

In the last Congress, a Senate version of this legislation (S.3205) took a different approach that would require wilderness managers to determine which routes in wilderness areas are open to mountain bikes. By statutory command, wilderness managers would have to put their thumb on the scale in favor of mountain bikes.

Both bills are bad and should not become law.

Arguments For and Against Bikes in Wilderness

This is not a new issue for wilderness advocates. The Spring 2003 issue of Wild Earth published a forum on wilderness and mountain bikes that included articles on all sides of the issue. My article (“Which Way?”) argued that wilderness advocates need to make limited accommodations for this nonmotorized recreation use. Other commentators in the same issue (distinguished conservationists Doug Scott, Dave Foreman, Brian O’Donnell, and Michael Carroll, and mountain bike and wilderness enthusiast Jim Hasenauer) had differing views. I suggest that the conservation community’s inflexibility about mountain bikes in wilderness is not serving our long-term political interests, let alone the protection of the wilderness resource.

Arguments against mountain bikes in wilderness areas need to be kept in perspective. In terms of environmental and trail impact, horses are worse than mountain bikes. But horses are tolerated because of a long American tradition of accommodating traditional uses. The Wilderness Act of 1964 accommodates horse use because horse use was long established in the areas that went into the National Wilderness Preservation System. Mountain biking has become an established use in many areas conservationists want to add to the wilderness system.

Anti-mountain-bikes-in-wilderness people will generally cite matters of public safety. They will tell a tale of a mountain biker careening down a trail and nearly running over a poor grandmother out enjoying the wildflowers. A better story to make such a case would be the one about the mountain-biking Forest Service employee who ran into a grizzly bear around a blind curve and did not live to tell about it. But society has not banned vehicles (including bicycles) because they sometimes hit pedestrians. It’s a matter of risk and, more important, a matter of personal responsibility.

Of course, one could argue that since allowing mountain bikes in wilderness areas has been successfully resisted for the past nearly three decades, it can be successfully fended off forever. This thinking, to use a mechanized transport analogy, is like driving forward while looking in the rearview mirror, which works as long as the road continues to be straight. If things never changed, we would have no history. But roads—both real and metaphorical—turn. Demographics are not on the side of the no-mountain-bikes-in-wilderness-areas crowd.

The political base of wilderness advocates who actively use roadless areas that should be in the wilderness system is an aging, and therefore declining, demographic. As we inevitably age, we turn from feet-on-the-ground activists to armchair activists and, therefore, our political power is just a bit less. The younger generations from which the replacement wilderness advocates must come are either focused on other things (such as climate change and urban environmental issues) or simply won’t be advocating to establish wilderness areas that ban their beloved mountain bikes.

For the most part, mountain bikers are part of the conservation base. They are lovers of nature and of the wild, just like wilderness advocates. However, wilderness designation can end up excluding mountain bikers from areas they enjoy now. Wilderness advocates should not want to drive human-powered mechanized recreationists into the arms of fossil-fuel-powered motorized recreationists. As mountain bikers overwhelmingly favor the conservation of the area, they should be in the conservation camp, not the exploiters gang. It is in the best interests of wilderness, and therefore wilderness advocates, to keep them there.

In the near term (which may be decades), wilderness advocates can probably be successful in staving off mountain bikes in wilderness areas. But probably not in the long term. And at what cost?

The cost paid today is land that is wilderness in fact and that should be wilderness in law but politically cannot be. Other congressional conservation designations can be found in many, but certainly not all, cases. The result is that de facto wilderness remains open to logging, mining, and off-road vehicles.

Wilderness-Lite” Not the Solution

Wilderness advocates have long feared and fought repeated and sustained efforts by some in Congress to offer up an “alternative” to wilderness areas, perhaps called a “primitive backcountry area” or “dispersed non-motorized recreation area” that accommodates some use (mountain bikes, off-road vehicles, etc.) the Wilderness Act does not. Wilderness advocates fear that if Congress ever does establish this “wilderness-lite” category, it will portend the end of the expansion of the National Wilderness Preservation System. They are probably right.

Mountain bike advocates are advocating designations of areas that won’t be roaded, logged, and/or mined—but will accommodate mountain biking. The premier advocacy organization for mountain bikers is the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA). The IMBA attitude toward mountain bikes in wilderness areas is, to their credit, nuanced. IMBA favors “similar prescriptions like National Protection Area, National Scenic Area, National Recreation Area, National Conservation Area, National Monument and other designations to preserve the land.”

Consider a national recreation area (NRA), a designation that generally precludes new roads and commercial logging and generally is designed to conserve and restore nature. From a conservation standpoint, an NRA should be viewed as an overarching conservation designation that conserves and restores entire mountains and/or whole watersheds, if not entire landscapes. Wilderness and wild and scenic rivers should be designated within NRAs as underlying conservation designations.

Don’t get me wrong. I love NRAs and believe there should be a national system of them. However, they are a complement to, not a substitute for, wilderness and wild and scenic rivers.

IMBA goes on to say

When proposed Wilderness areas include mountain biking assets and opportunities, IMBA advocates for and vigorously negotiates using a variety of legislative tools, including boundary adjustments, trail corridors and alternative land designations that protect natural areas while preserving bicycle access. IMBA can support new Wilderness designations only where they don’t adversely impact singletrack trail access for mountain biking. . . .

IMBA’s Board of Directors recently reasserted IMBA’s longstanding position on trail access, public land conservation and federally designated Wilderness. IMBA’s board has determined that IMBA’s mission is best served by reiterating our strong commitment to collaboration and further diversifying and strengthening our broad partnerships that serve as the backbone of advocacy success for our chapter network. IMBA will not support any broad efforts by any organization to amend the existing Wilderness Act in its entirety or the federal land management agencies’ regulations on existing Wilderness areas as these are not strategically aligned with achieving our long-term mission.

However, with a trail by trail, case by case basis, in conjunction with local chapter efforts, IMBA will pursue Congressional legislation to adjust existing wilderness boundaries that reopen trails currently closed to people riding bicycles.

Tweaking Wilderness Act

The Wilderness Act is neither the 11th Commandment nor the 28th Amendment. It was the best that could be done at the time. Rather than eschewing entire new wilderness areas, bisecting wilderness with mountain bike trail corridors, and/or leaving wilderness acres on the political table and open to exploitation, wilderness advocates need to recognize that it’s time to heal the split between human-powered recreationists who favor feet and those who favor the wheel. Conservation has real enemies to worry about. The tread of a mountain bike pales in comparison to the tread of a bulldozer.