Top Line: While most Mountain Westerners favor the conservation of public lands, most of their elected officials are either openly hostile or passively wimpy.

Figure 1. The annual State of the Rockies Project Conservation in the West Poll tells us a lot about how voters in the Mountain West view public lands conservation. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Every year, the State of the Rockies Project at Colorado College polls voters in eight “western” states on their attitudes toward the conservation of nature and the threats to the same. (As a denizen of a Pacific West state, I put quotation marks around “western” because the polling is limited to the Mountain West states, as shown in Figure 2.) The 2024 poll points up a large disconnect between voter attitudes and public lands conservation in the West.

Figure 2. The westernmost states of the American West are not included in the Conservation in the West Poll. The polling began in 2011 with the five states shown in blue. Arizona was added in 2012, Nevada in 2016, and Idaho in 2018. It’s 2024 and I’m tired of waiting. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Even though most Mountain Westerners favor the conservation of public lands, candidates who lean toward conservation continue to lose (or don’t even run), and elected officials and land managers are neither reading nor heeding the polls. How do we explain this disconnect, and what can be done to address it? I argue that one essential step is for conservation organizations to rethink their nonprofit status so as to be able to weigh in on elections and thus best represent their members.

What the 2024 Conservation in the West Poll Shows

The Conservation in the West Poll employs two polling firms, one that specializes in Republican candidates and one that focuses on Democratic candidates. Bottom lines: voters are increasingly concerned about nature (Figure 3), and an ever-greater percentage of voters say that ensuring its protection is an important factor in choosing who to vote for (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Concern about nature is on the rise among voters in the Mountain West. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Figure 4. “Western” voters increasingly favor protecting nature on public lands rather than favoring energy production there. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

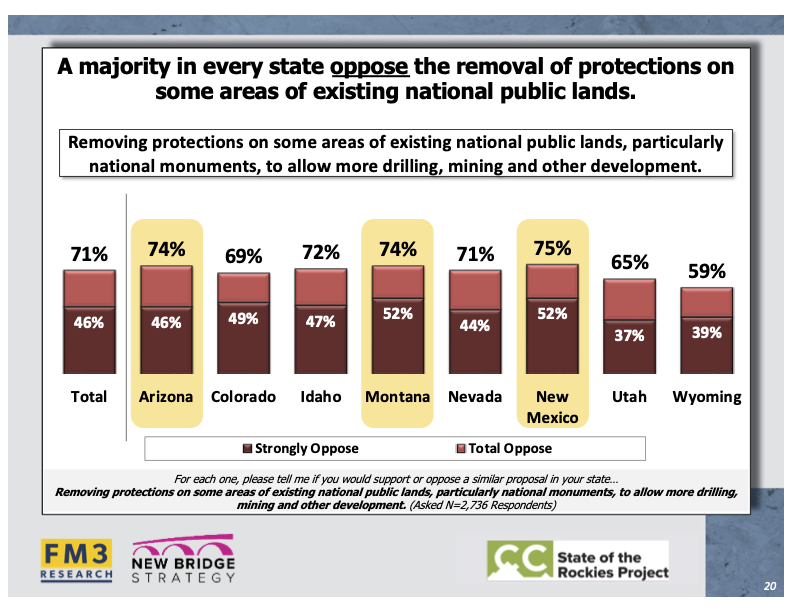

“Westerners” strongly support conservation on public lands (Figure 5), don’t want existing conservation protections weakened (Figure 6), and want more land protected for the benefit of this and future generations (Figure 7).

Figure 5. “Westerners” strongly support policies that protect public lands. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Figure 6. Voters don’t want existing public land conservation protections weakened. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Figure 7. Voters want public land conservation protections strengthened. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

The Disconnect Between Voter Beliefs and Reality

Unfortunately, there is a disconnect between what voters believe and reality. The State of the Rockies Project reports, “Notably, clean energy is seen as compatible with preserving natural areas, wildlife habitat and community character” (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Voters see clean energy and nature conservation as compatible. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

If only what voters believed (pronounced “wished”) were true! While it depends a lot on the siting of new energy facilities (solar panels can live in the desert or on rooftops, but desert tortoises can only live in the desert), large-scale renewable energy development (such as geothermal power plants, solar panel compounds, and wind farms) destroys or degrades wildlife habitat. A sage-grouse appreciates not a whit that the electrons coming from a new power plant that destroyed its habitat are green rather than brown.

The conservation community does itself no favors by embracing such happy talk.

The Disconnect Between Voters and Elected Officials

There is also a disconnect between what voters say they want and what elected officials are doing. If 74 percent of Republicans, 87 percent of independents, and 96 percent of Democrats (Figure 9) say that “a public official’s position on conservation issues will be an important factor in determining their support,” why the hell do Republicans who do not favor conservation of public lands dominate most state legislatures and statehouses in the Mountain West? Why are most elected Democrats effectively missing in action in the war to save the earth?

Figure 9. A vast majority of voters of all parties say it is important to them what their elected officials are doing on conservation issues. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Consider Utah, perhaps the state with the greatest disconnect between what the voters want (according to polling) and what the voters get (according to politics). Utahns, by a four-to-one margin, favor 30x30 (conserving 30 percent of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030) (Figure 10).

Figure 10. While more Coloradans feel more strongly about it than Utahns, 83 percent of both say they support 30 percent of the nation’s lands and waters being conserved by 2030 (30x30). Source: State of the Rockies Project.

While half of Utahns think climate change is a very serious problem (Figure 11), you wouldn’t know that by the behavior of Utah governments. While four-fifths of Utahns favor more national parks, monuments, and wildlife refuges, the Utah State Legislature is seeking to overturn recent national monuments. For example, the State of Utah is currently suing to destroy the Bears Ears National Monument, established by President Obama, gutted by President Trump, and restored and improved by President Biden (Figure 12).

Figure 11. What voters in the Beehive State say they want done about nature/climate/environment/pollution/energy doesn’t match the behavior of Utah governments. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Figure 12. Bears Ears National Monument is wanted by most Utah voters and not wanted by most Utah elected officials. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

How to Explain the Disconnect?

What accounts for this huge disconnect between what voters in the Mountain States say they want and what their elected officials are doing?

Is it that while voters say the environment/nature/climate/whatever is very important to them, in fact it is not actually the case when they vote?

Is it that pro-nature voters don’t know which candidates are good or bad on the environment, because they haven’t been told?

Is it that elected officials don’t vote for the environment because they don’t get campaign contributions for doing so, but they do get campaign contributions for voting against nature?

Is it because special interest money (dark or otherwise) contaminates elections?

Is it because conservation was for more than a century a bipartisan issue but is no longer?

Is it that the Republican Party has unabashedly become the anti-environment party?

Is it that the conservation community has become totally aligned with the Democratic Party?

Is it because the Democratic Party takes the votes of conservationists for granted as conservationists have nowhere else to go?

Is it because if Republican elected officials do the right thing, they get little love from enviros and much hate from the forces of darkness?

Is it because the conservation community is fundamentally barred by its tax status from effectuating political change?

Yes.

The Conservation Community’s Wrong Mothership Model

A big problem is that the conservation community has chosen the wrong tax status. Almost all conservation organizations operate under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), a provision that both (1) severely limits the amount of money they can spend seeking to influence legislation, and (2) totally forbids the organization from engaging in election campaigns.

Section 501(c) organizations are nonprofits, of which there are various types. (c)(3) (charitable) nonprofits voluntarily eschew their First Amendment rights in exchange for a tax exemption. (c)(3) nonprofits don’t pay taxes on their income, and people who give to (c)(3) nonprofits can deduct their contributions from their income subject to tax.

Another tax status available to nonprofit organizations is 501(c)(4). (c)(4) (social welfare) nonprofits don’t pay taxes on their income, but contributions to a (c)(4) are not tax-deductible for the donor. Not only is the amount of lobbying (seeking to influence legislation) a (c)(4) can undertake is not limited as with a (c)(3) organization, but also, according to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS):

IRC 501(c)(4), (c)(5), and (c)(6) organizations may engage in political campaigns on behalf of or in opposition to candidates for public office provided that such intervention does not constitute the organization’s primary activity.

A 501(c)(5) organization is a labor union (or an agricultural organization), and a 501(c)(6) belongs to the category “business leagues, chambers of commerce and real estate boards.” So trade associations, trade unions, and farm lobbies (which are often anti-environment) can engage in political activity, but pro-environment organizations that have chosen the wrong tax status cannot. Why have most of the latter organizations chosen 501(c)(3) status? Saving nature and the climate is not charity but is fundamental to social welfare.

Most advocacy / political change organizations operate primarily as (c)(4)s, but not the conservation community. A few (c)(3) conservation organizations do operate companion (c)(4) organizations, but these are always an afterthought, poorly funded and operated as the occasional sideshow. The (c)(4) is usually named the same as the (c)(3) but with “Action” or “Action Fund” at the end of the name (for example, the NRDC Action Fund, the Center Biological Diversity Action Fund). Some (c)(3) organizations, like Defenders of Wildlife, once had a (c)(4) but let it wither or die.

Conversely, most other social change entities—be they on the right or the left—operate primarily as (c)(4)s, while having a (c)(3) appendage to acquire money that they can get only if such is tax-deductible to the donor.

The (c)(3) mothership model for the conservation community is insane for the following reasons:

1. Elections matter. A lot. More than anything else if one is actually seeking change.

2. Most donors care more about their contributions being used effectively than being used deductively. Most of us don’t give enough money to charity to benefit from itemizing it on our taxes (we take the standard deduction instead), so we receive no tax benefit from giving hamstrung money to (c)(3)s.

3. To accommodate those who “need” the tax deduction (a questionable premise, given the diminished value to the cause one believes in), mothership (c)(4)s have a handy companion (c)(3) available.

One of the many reasons David Brower was fired as executive director of the Sierra Club in 1969 was that he caused the IRS to revoke the club’s (c)(3) status in 1966. That year, Brower used Sierra Club c)(3) funds to place full-page ads (it was a big thing back then) in the New York Times and the Washington Post opposing dams on the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. (The ads asked, “Should we also flood the Sistine Chapel so tourists can get nearer the ceiling?”)

The Sierra Club became a (c)(4), and thanks to Brower’s overstepping, there are no such dams on the Colorado today. The Sierra Club Foundation, which was waiting in the wings, became the tax-deductible (c)(3) receptacle for the Sierra Club conglomerate. (The club also has a political action committee and once had a legal defense fund, since spun off.) The 501(c)(3) revocation by the IRS was the single most important factor making the Sierra Club the most powerful national conservation organization to this day.

If Only We Had the Time

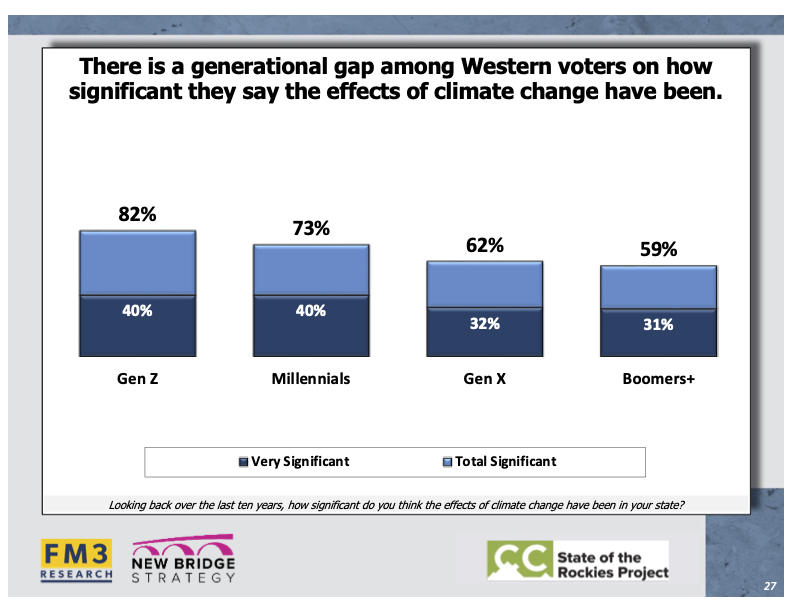

The good news is that the younger the voter, the more likely it is that the voter is pro-nature-and-climate and anti-pollution (Figure 13). The bad news is that nature and the climate cannot wait for boomers to age out (it sounds nicer than die out, don’t you think?) and for younger generations to become a larger part of the electorate.

Figure 13. Younger voters in the Mountain West are more concerned than older voters about the effects of climate change. Source: State of the Rockies Project.

Bottom Line: Conservation organizations need to rethink their nonprofit status to allow effective legislative and political engagement. Now.

For More Information

Alliance for Justice. Comparison of 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) Permissible Activities (pdf).

———. Election Year Activities for 501(c)(4) Social Welfare Organizations (pdf).

Colorado College, State of the Rockies Project. 2024 Conservation in the West Poll (web page).

Kerr, Andy. September 30, 2016. The Bipolar State of Utah and National Monument Designation. Public Lands Blog.

———. December 1, 2017. Public Lands Conservation in Congress: Stalled by the Extinction of Green Republicans. Public Lands Blog.