The slightest breeze will make quaking aspen leaves dance. The leaves’ bright green upper surfaces contrast sharply with their dull green undersides against the backdrop of their white bark and a blue sky. Viewing golden quaking aspens on a crisp and clear autumn day is a powerful reminder that all is not wrong in the world.

The largest organism on Earth is one quaking aspen clone with more than forty-seven thousand stems (trees). This organism is being cow-bombed and otherwise abused. The cow-bombing, if not stopped, might well eventually result in the demise of the organism. As goes this singularly large quaking aspen clone, so may go the rest of the quakies in the American West.

Figure 1. Quaking aspens in Lamoille Canyon, Nevada. Source: Wikipedia.

A Wide-Ranging Tree and a Keystone Species

The quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) is the most widely distributed tree in North America (Map 1). The species ranges from Alaska to Newfoundland and from Virginia to northern Mexico. It is found at sea level in the northern end of its range and at 1,500 feet elevation in the southern end. In Oregon, the brilliant spring green and magnificent golden fall foliage of quaking aspens can be seen in the Cascades, the East Cascades Slopes and Foothills, and the Blue Mountains ecoregions. Only a few aspen stands occur in the Coast Range and the Klamath Mountains. More can be found in the high ranges of the Oregon desert such as Steens Mountain, Hart Mountain, and others.

Map 1. The range of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). Source: Wikipedia.

Aspen forests are biologically rich and provide cover as well as nesting and feeding habitat for a wide range of birds. Rabbits eat the bark, and grouse feed on aspen’s winter buds. Deer and elk heavily graze aspen twigs and foliage, as they do the associated understory. A quaking aspen grove may have 3,000 pounds of understory growth per acre, compared to 200 pounds per acre in a conifer forest. Humans like to carve their initials and ideograms in the bark. Those carved by lonely late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century sheepherders can still be found and are often sexual in nature.

Aspens grow in wet areas and are a favorite of beavers. Both quaking aspen and beaver are keystone species, meaning their existence makes an outsized contribution to a diversity of habitats and therefore to a diverse array of species that depend on such habitats. For example, many woodpecker species generally love aspen stands. A stand of aspen trees adjacent to a pond full of beavers is a wonderfully biologically diverse condition.

While individual trees (which are actually stems of a much larger, underground organism) are relatively short lived, a stand of aspens is not. Aspen trees typically grow twenty to seventy feet tall and live seventy to ninety years. However, an aspen grove can survive indefinitely even if it burns occasionally. Burning can be beneficial in knocking back invading conifers. Within six weeks of a burn, aspen shoots will rise through the forest floor from the clonal rootstock below and have a distinct advantage over any conifer seeds from cones.

If you see several clumps of aspen trees, each with a distinctive color, know that each chromatic cluster is a clone (genetically identical) from the same original tree that sprouted from a seed thousands of years before.

Cow-Bombing of Aspen Groves

In the American West, the original 9.6 million acres of quaking aspen is down to just 3.9 million acres. The decline of quaking aspen in the American West has been severe and is mostly attributable to the onslaught of domestic livestock. Any amount of grazing by domestic livestock is harmful to aspens, as the bovines trash the understory and nip off all the replacement shoots from the root system.

Some examples:

• In Oregon’s Malheur National Forest, aspens have been reduced by 80 percent from historic levels by livestock grazing.

• In Utah’s Fishlake National Forest, aspen cover has declined 60 percent from historical levels.

• Many aspen stands in northern Nevada have not regenerated in more than a century and are dying out.

• In the late 1880s with the arrival of livestock, the rate of new individuals being added to aspen groves (also called recruitment rates) in what would become the Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon plummeted. After livestock were banned from the refuge in 1990, recruitment rates increased by an order of magnitude.

Like domestic ungulates such as cattle and sheep, native ungulates such as deer and elk can have deleterious effects on quaking aspen reproduction. However, there are some important differences:

• Quaking aspen co-evolved with native ungulates and is not evolutionarily equipped to address an onslaught of alien livestock.

• The individual intensity of grazing pressure from native ungulates is far less than from domestic ungulates.

• The collective intensity of grazing pressure from native ungulates is not only far less overall but also spread out over the year.

• Wolves and other large predators keep native ungulates within ecological bounds, while wolf presence near domestic livestock can be a capital offense.

Range conservationists [sic] and range scientists [sic]—professions generally populated by those who don’t have the means to be ranchers themselves but nonetheless love to wear hats, boots, and buckles—tell us that one cow and calf consume as much forage as about five deer, pronghorn antelope, or bighorn sheep, or as much as about two elk. These figures assume a standardized cow of 1,000 pounds. Today, the average cow is 1,384 pounds, a 40 percent increase. Native ungulates have not increased in size, so the discrepancies are actually far greater.

Fire Suppression and Aspen Groves

While domestic livestock are unquestionably a large part of the problem, another culprit is Smokey Bear. Aspens sprout profusely after a fire. The first year after a burn may see 150,000 sprouts per acre. A few years later, the aspens will be a few feet tall with a density of 40,000 to 50,000 sprouts per acre.

The suppression of fire throughout most of the West due to federal policies allows shade-tolerant conifers to slowly invade aspen stands. The conifers then outcompete new aspen shoots by using the aspens’ biology against them. Live and healthy adult aspens send a growth-inhibiting hormone down their trunks and into their roots to discourage excessive shoot production, thereby inhibiting the growth of young aspens. When adult aspens die, this hormonal impediment to new shoots ceases. If conifers have overtaken the forest floor by the time adult aspens die out, new aspen shoots cannot get established and the aspen stand may eventually be replaced by conifers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) (foreground) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) (background) on the Ochoco National Forest in Oregon. While aesthetically pleasing, the image is disturbing if you note the utter lack of any aspen replacement stems .Source: Sandy Lonsdale. First appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness (Timber Press, 2004).

The Pando Problem, a Case in Point

It is the nature of quaking aspen trees to reproduce most often from shoots that arise from the roots of existing trees. DNA analysis has shown that a particular cluster of aspens in the Fishlake National Forest in Utah is actually one big-ass (a scientific term) clone. It’s one single organism of ~106 acres in extent with an estimated weight of more than 6,600 tons, manifesting with ~47,000 “ramets” (stems, commonly understood to be trees). The organism is called Pando, Latin for “I spread out.”

The age of Pando (a.k.a. The Pando or the Pando Clone; I like to think we’re on a first-name basis though we’ve yet to meet) is in scientific dispute, with estimates ranging from 8,000 to 10,000 years up to 80,000 years. Pando did not spontaneously arise in the 1880s, as speculated by someone with an increment borer and a forester mentality who thought he was coring a few trees rather than a few ramets of a much larger single organism.

While ramets age out and die and fall over, under normal conditions such ramets are replaced. For Pando to survive in the long run, the number of new ramets must be at least equal to the number of old ramets. But alas, the world’s largest organism is slowly dying from repeated intense livestock grazing. Even though the aspen is the state tree, Utah has not been kind to the quaking aspen (of course, neither has Oregon been kind to the Douglas-fir).

Given the grazing problem and that it is the world’s largest organism, the Forest Service has facilitated some experimental fencing designed to exclude all ungulates or just large (code for cows) ungulates (Figure 3). The scientific evidence is pretty clear that domestic livestock are the overwhelming cause of inadequate recruitment of new ramets (commonly known as shoots or suckers). While native deer also play a role, it is minor and would be not an issue if not for being compounded by cows (see below).

Figure 3. Red line: outline of the Pando Clone. Yellow and blue lines: fences to keep out mule deer and livestock for research purposes. Tan line through the middle of the Pando Clone: State Highway 25. Fish Lake, Utah, at lower right. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Pando has not only suffered the simultaneously chronic and intense indignity of being cow-bombed for going on 1.5 centuries but is also bisected by a highway and defiled by recreational development. Finally, its ramets can be affected by the sooty bark canker (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The sooty bark canker, which hastens the demise of older quaking aspen stems. Source: USDA Forest Service.

A Damning Report on a Damnable Situation

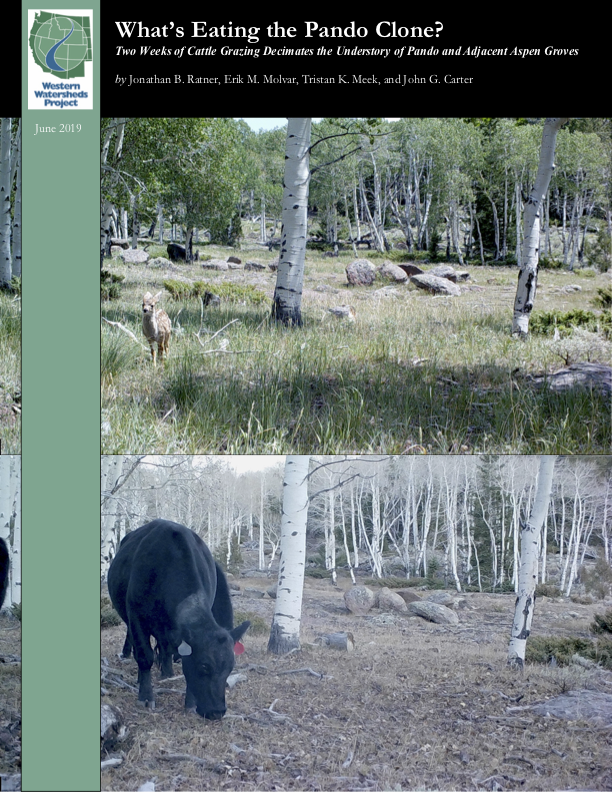

The Western Watersheds Project has produced an excellent report entitled “What’s Eating the Pando Clone? The subtitle of the June 2019 report says it all: “Two Weeks of Cattle Grazing Decimates the Understory of Pando and Adjacent Aspen Groves.” The report’s four authors—Jonathan Ratner, Erik Molvar, Tristin Meek, and John Carter—are to be commended.

Figure 5. The damning and well-documented report from the Western Watersheds Project (worthy of a donation from you). Take a moment to study the before and during cow-bombing pictures. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

The report not only examines the literature on the effects of ungulates on aspen groves but also includes images from four time-lapse cameras set up by the researchers (see edited sequences here) to gather evidence on just which ungulates are eating up all the forage (including new aspen shoots). Below are some images dating from late spring to late fall that show the effects of the annual autumn bovine bacchanal on one spot in the Pando Clone (Figures 6 through 11).

Figure 6. Camera 2 on May 12, 2018, at 45°F. Spring hasn’t yet fully sprung, but it is springing. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Figure 7. Camera 2 on June 17, 2018, at 72°F. Summer starts in a few days. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Figure 8. Camera 2 on August 16, 2018, at 72°F. Summer well under way. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Figure 9. Camera 2 on October 2, 2018, at 54°F. The aspens are turning and the grasses are curing, just before the cattle arrive. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Figure 10. Camera 2 on October 9, 2018, at 36°F. The bovines are only there a few weeks. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Figure 11. A ground shot from the location of Camera 2 on November 22, 2018. Bovine calling cards, including some from previous years, are evidence of the cows’ passing through. (Please don’t call them cow pies; they are not pies made of cow, but feces from a cow.) Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Charts 1 and 2, reproduced from the report, make clear the culpability of cattle in the decline of Pando.

Chart 1. Forage use levels before livestock entry and after removal, determined from cameras sited within the Pando Clone. Although the bovine bulldozers are defiling Pando for only a few weeks, they consume most of the forage in that time. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

Chart 2. Deer versus cattle animal units (AUs) by week within an unfenced portion of the Pando Clone.Total deer consumption of forage is not only far less than total livestock consumption of forage, deer use is spread throughout the year. Source: Western Watersheds Project.

What to Do

Fence off the world’s largest organism from domestic livestock.

Reintroduce wolves for natural regulation of deer numbers.

Of course, such would be equally appropriate for the world’s second largest organism, as well as the third, not to mention the fourth . . .

May I suggest that you also make a donation to Western Watersheds Project so they may continue their fine work. Because of their work at the leading edge of public lands conservation by seeking to end abusive livestock grazing, Western Watersheds has received relatively little foundation support. It’s up to us.

Note: Some of the text in this Public Lands Blog post is drawn from Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness (Timber Press, 2004), by the author.

Figure 12. Quaking aspens at Kebler Pass, Colorado. Source: USDA Forest Service.