Take a gander at your favorite statewide maps, on paper or in Google Maps, and you may be left with the impression that those green polygons labeled National Forest are indeed solid expanses of national forest. In the West and Alaska, mostly yes; in the East, not so much.

Only 54 percent of the lands within the official boundaries of eastern national forests are federal public lands. Compare that to 90 percent of western national forest lands and 95 percent of Alaskan national forest lands. Nationally, only 83 percent of the Forest Service green on maps is Forest Service land. The poor Uwharrie National Forest in central North Carolina (I hadn’t heard of it either) is only 23.25 percent national forest land. The Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia is typical at the coincidental 54 percent (see Maps 1 and 2). The rest of the lands within the official boundaries are undeveloped private timberlands.

Map 1. Alas, the solid green on this Monongahela National Forest locator map is only 54 percent federal land.

Map 2. Taking a closer look at the Monongahela National Forest, we see that much of the land within the bright green line (the national forest boundary) is unoccupied private land, which is threatened by logging and development. The most prevalent green shading is federal public land (darker green is designated wilderness). The thick gray border is the boundary of the Spruce Knob–Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area, established in 1965.

How the Eastern National Forests Came to Be

National forests in the East generally took one of three paths to creation: under authority of the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act of 1937, and/or the Weeks Act of 1911.

While most of the federal public domain is in the eleven western states, eight national forests were carved out of the federal public domain under the Forest Reserve Act of 1891:

• 1907: Arkansas, AR

• 1908: Choctawhatchee and Ocala, both FL; Minnesota, MN; Ozark, AR

• 1909: Marquette and Michigan, both MI; Superior, MN

Four other forests were established from lands acquired under the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act of 1937:

• 1959: Oconee, GA; Tombigbee, MS; Tuskegee, AL

• 1960: St. Francis, AR

Though generally not considered part of the eastern U.S., but nonetheless part of the U.S. is the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The El Yunque National Forest was first established as a forest reserve in 1876 by King Alfonso XII of Spain. The land was then designated by the U.S. Government as the Luquillo Forest Reserve in 1903 and as a national forest in 1906. It was renamed the Caribbean National Forest in 1935 and the El Yunque National Forest in 2007.

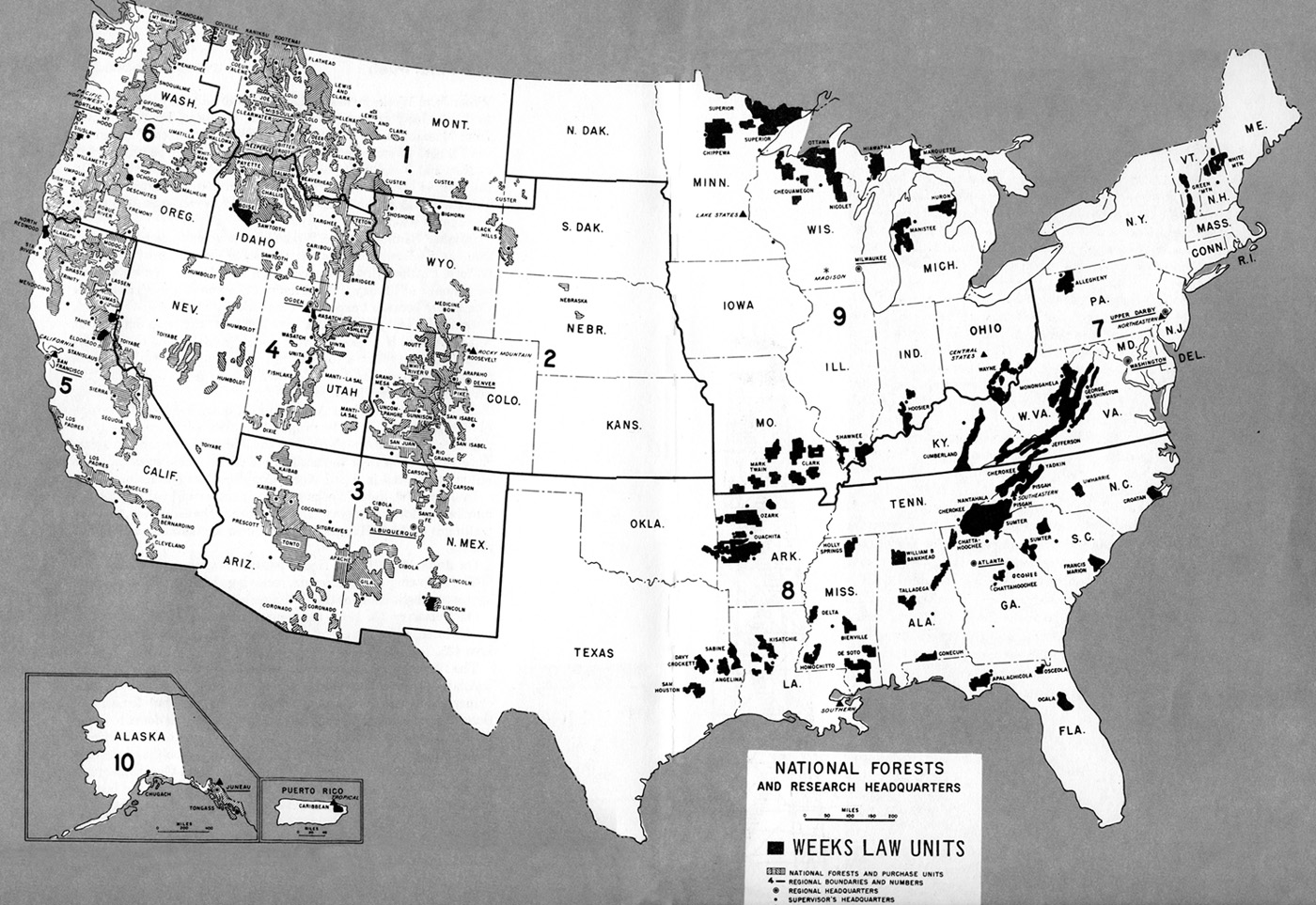

Last, and certainly the opposite of least, is the Weeks Act of 1911. Most national forests in the eastern United States were established pursuant to the Weeks Act (see Map 3).

Map 3. Notice that the Weeks Act has also been used to reconvert private timberlands in the West to public forestlands.

Starting in the 1880s, local citizens were becoming more and more concerned about the rapacious logging of forests (known as “cut and run,” as in cut it all and then abandon the land) that was causing the despoliation of watersheds, soil, wildlife, and scenery in the East. The logging was so bad that numerous state legislatures passed measures inviting Congress to establish federal forests in their states. Most eastern states had few or no public domain lands, so if there were to be national forests, they would have to be bought.

What enabled the purchase of these lands was the Weeks Act, named after Republican Rep. John Wingate Weeks (1860–1926) of Massachusetts (Picture 1). Weeks had an interesting life: born in New Hampshire, he taught school, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, served in the Spanish-American War, and was first chief of the Orlando, Florida, fire department; he served as alderman and then mayor of Newton, Massachusetts; and he finally became a Member of Congress, a U.S. Senator, and the U.S. Secretary of War. In the Senate, among other things, he chaired the Committee on the Disposal of Useless Executive Papers. His ashes are interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Signed into law by President Taft, the Weeks Act authorized and directed the Secretary of Agriculture (through the Forest Service) “to examine, locate, and purchase such forested, cut-over, or denuded lands within the watersheds of navigable streams as in his judgment may be necessary to the regulation of the flow of navigable streams or for the production of timber.” Such lands could only be acquired with the consent of the affected state legislature. To ensure the constitutionality of the law, it was based on aiding the navigability of streams, which was necessary for interstate commerce.

The original law allocated $9 million to purchase 6 million acres of land in the eastern United States, which works out to $1.50/acre. By the time the National Forest Reservation Commission, established by the act to consider and approve the purchases, transferred its responsibilities to the Secretary of Agriculture in 1976, 20,782,632 acres had been purchased for $118,054,248, or $5.68/acre (not adjusted for inflation).

Forty-two national forests (some have been merged since) in twenty-three eastern states were established under the Weeks Act (see Table 1). While primarily used to acquire eastern national forests, the Weeks Act applies nationally and has been used to acquire national forest lands in western states as well (see Table 2). The success of the Weeks Act and its contribution to the conservation of natural resources in the eastern United States has been enormous.

Work Left to Do

Private timberlands in the eastern U.S.—both inside and outside of the official national forest boundaries—are threatened by logging and/or development. The best way to conserve them for this and future generations is for them to be in public ownership.

The Weeks Act is still the law of the land. Congress should appropriate money for the Forest Service to acquire undeveloped private timberlands within the official national forest boundaries. Additionally, more national forests should be established in the few states that don’t have them (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Hawai’i) and also states that do.

For more on the Weeks Act see the Forest History Society’s Weeks Act centennial issue of Forest History Today and the USDA Forest Service’s web page Weeks Act Centennial 2011. See also “The Lands Nobody Wanted: The Legacy of the Eastern National Forests,” by William E. Shands, and “The Eastern Forests,” on the Forest History Society’s U.S. Forest Service History web page.

Thanks John!

Picture 1. Republican Rep. John Wingate Weeks (1860–1926) of Massachusetts.