Only public ownership can reliably, certainly, and durably allow certain natural processes the room they need.

—Carl Pope, Executive Director, Sierra Club

In the West, we have extraordinary landscapes but they are not complete. When many of the boundaries of our national parks and forests were established years ago, we didn’t have the science to tell us more land was needed. Now we have the science and we need to act on it.

—Bruce Babbitt, former Secretary of Interior

History has shown we cannot rely on the private sector to conserve forests, protect drinking water, and provide other public values, including wildlife habitat, recreation opportunities, and scenic views. The private values of timberlands are in conflict with these public values and are driven by a desire to maximize profit, return on investment, and net present value. If the public wants to have those public values, these conservation responsibilities must be borne mostly by the public—not the private—sector.

Gone is the time when most private timberlands were owned by companies that viewed them as a feedstock to the mills they also owned and when some were even logged at conservative rates because the owner wanted production sustained over time. Today it’s all about ownership structures that minimize taxes and maximize financial return while also hedging against inflation and diversifying one’s portfolio. The ownership of most large blocks of private timberlands is structured as either a timber management investment organization (TIMO) or a real estate investment trust (REIT). A typical TIMO is structured as a ten-year investment, considered “long term” on Wall Street but not long in the life of a tree—even one destined to be logged as soon as financially possible.

Most industrial timberland in the United States has now been logged at least three times—if not four or six times. Where huge trees of several species once stood are now stunted monoculture plantations more ecologically akin to a cornfield than a forest.

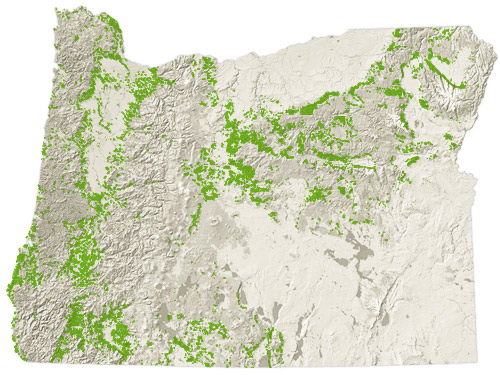

5,933,000 acres of Oregon is large private industrial timberland.. Source: Oregon Forest Resources Institute.

In Oregon alone, nearly six million acres of private timberland (roughly the size of the Deschutes, Mount Hood, Willamette, Winema, Rogue River, and Umpqua national forests) could be reconverted to public forestland (Map 1). There are also nearly 4.7 million acres of small private timberland holdings. The State of Oregon should acquire large amounts of private timberlands from willing sellers and give them over to the United States to be managed as national forests. This should be done because it is ecologically imperative, socially desirable, economically rational, and fiscally feasible. The state must reinvest in and maintain its natural infrastructure just as does its other infrastructure.

4,668,000 acres of Oregon is private timberland. Source: Oregon Forest Resources Institute.

As population grows, we will need more real forests. Oregon enjoys many of the state parks it has today because, going on a century ago, Sam Boardman, the first superintendent of Oregon State Parks, convinced Oregonians to buy public parkland when it was cheap though not yet needed. Today, most politicians cannot even convince Oregonians to pay for what is needed now, let alone in the future. Private timberland is not inexpensive now, but it will not get any cheaper.

Sam Boardman, the first director of Oregon State Parks.

Among the ecological, watershed and recreational achievements that could be realized with the acquisition of more public forestland is a Willamette Valley Greenbelt—equivalent to a band of parks like Silver Falls State Park surrounding the Willamette Valley in the foothills of the Cascade and Coast ranges—envisioned by former Oregon State Parks director Dave Talbot to complement the Willamette River Greenway. A protected forest corridor running from Portland’s Forest Park to the Pacific Ocean could also become a reality.

In 1977, I visited Kloochie Creek in Clatsop County near where the nation’s largest known Sitka spruce then stand and where the largest known Douglas-fir once stood. A Crown Zellerbach executive said of what had been a magnificent old-growth Douglas-fir forest of 12-foot-diameter trees, where there are now only clear-cuts and plantations, “We knew in the 1950s we had to log it then, or it would be a national park by now.”

In the 1920s, the Commonwealth of Virginia acquired some cutover, burned-off, mined-out, grazed-down, plowed-up mountains and gave them to the United States in order to, as the National Park Service said, “invite nature back.” It was a radical idea, but the creation of Shenandoah National Park is now considered a very reasonable thing to have done. Since it takes several hundred years to regrow 12-foot-diameter Douglas-firs, even in the Oregon Coast Range, we must start reconverting private timberland to public forestland immediately.

The State of Oregon could finance this reconversion of private timberland to public forestland. At $3,000 per acre (a fair price for large acreages), the cost of purchasing two million acres of private industrial timberland is $3 billion. If the amount were borrowed at 4 percent for twenty years, servicing the debt would cost $444 million per year. A 6¢-per-gallon increase in the state fuels tax and equivalent increases in the weight-mile tax and DMV fees could easily pay the debt. This would be a logical exchange, because Oregonians would mitigate the climate change impacts of burning fossil fuels while conserving and restoring the state’s forests. Polluting carbon in the atmosphere would be transformed to carbon in trees that would eventually become old-growth forests again.

Here is another way to look at it. With (at the moment) four million Oregonians, the cost to acquire two million acres of public forestlands is less than $2 per week per Oregonian—or less than half the price of a decent latte or IPA. Here’s to restoring Oregon’s forests!